News about 3DR working with DJI to help enterprise users deploy and manage drone operations was a pretty big deal, for several reasons. Not only does it re-confirm 3DR’s commitment to the AEC industry, but it also provides professionals with a much easier approach to actually using these tools. The ubiquity of DJI hardware combined with the easy integration of professional tools like Site Scan means that many more organizations will be able to discover how they might be able to use this technology in the present and future.

Chris Anderson delivering his keynotes address at the Commercial UAV Expo

Exploring what that future might look like is something Chris Anderson, the

CEO of 3DR, did in a

recent article where he discussed why he hoped the future of drones is boring. What will it take for us to get there though? Is it enough to talk about the efficiency, safety and cost of drones when enterprises want to know what an investment in UAV technology will mean to their bottom line? How will we know whether or not we’re actually getting closer to this future where drones are considered “boring”?

These were just some of the details Chris discussed in the interview below. Read on to find out not just what the future of drone technology might look like, but what we need to focus on enabling and creating in order to get there.

Jeremiah Karpowicz: I want to focus on what it will mean to see drone technology transition into being this “boring” piece of technology that you’ve talked about, but do you think that concept runs counter to the stories about the billions of dollars drone technology possesses, which are still making headlines? Or are these kinds of numbers and stories inherently linked to this transition?Chris Anderson: They are absolutely linked, because that's how you get to a billion dollars. You don't get to a billion dollars by being a shiny toy or a bleeding edge technology. You get to a billion dollars by being an essential tool. The way you get to being an essential tool is that you go beyond the early adopters into something that just makes sense. You use it because it makes your job easier, or it saves money, or because it's so simple to use.

The job of technology in general is to extend the Internet. Period. That's what we all do. Some people extend it to your pocket or to your car or to your home, but the Internet is a great way to use aggregated data to make things smarter, and we use distributed sensors to make the Internet smarter. We extend the Internet into the air, and in our case specifically, we extend it into the built world.

The way you extend tech into the non-tech industry is to make it not look like tech. So if you can make it look like a box with a button, that's good. If it can be used by people with little to no training, that's also good. It's like taking electricity from a Tesla Coil to a wall outlet. You only get to a billion dollars when it's a wall outlet.

When you have conversations with potential clients though, how many are focused on that shiny new toy aspect of the technology over it being a practical tool? Do you find yourself needing to explain that the advantages associated with this technology are about the data, not the drone?The word "drone" gets us in the door, but it doesn't close the deal. What closes the deal is when you speak their language, not ours. Those are things like ROI, survey precision, design surfaces and engineering surfaces. Literally, the word "drone" doesn't come up again after the first two minutes of the conversation.

It's almost always going to be about the data because at this point, you can pretty much assume the device is going to fly, and the data is going to be recorded and stored properly, etc. It's crazy, given that I spent the first part of my venture with 3DR getting drones to the point where they could be considered a solved problem, but at this point they really are. The data is very much not a solved problem though.

The data is what allows us to speak their language, at that point, you're totally in their world and you understand their pain points. They'll say something like, "we have this really big land area that we have to survey, and right now it's kind of a laborious process," because they're literally counting things like trees and sewer covers, and they want to make it easier. So we're talking about those kinds of details, not the drone, because the drone is assumed.

Those kinds of details are what I wanted to focus on with you, because talking about how a drone can make things more "efficient" just doesn’t cut it anymore. In that regard, how does being able to define the impact of the technology relate to the measurement and management that drones enable? In the first wave of the drone world, we were taking pictures from the sky and then simply handing those pictures over. The reaction from professionals was they were nice, but they didn't know what to do with them. Those pictures weren't in the formats they used, or the labeling they used, etc. So it wasn't useful. That's why we wanted and needed to find out what would be useful. They educated us on what kind of measurement would actually pass the test in their industry.

As we transitioned from being one of the pioneers in getting robots to fly to now being one of the pioneers in making them useful, we've had to go through a long education process about what “useful” means. For the most part, useful doesn't simply mean pictures from the sky. What useful means is ensuring that the measurements we have are going to be accepted by a company’s employees, customers, clients, etc. Until we focused in on not just the precision, but also understand what precision matters to them, it was just a science project.

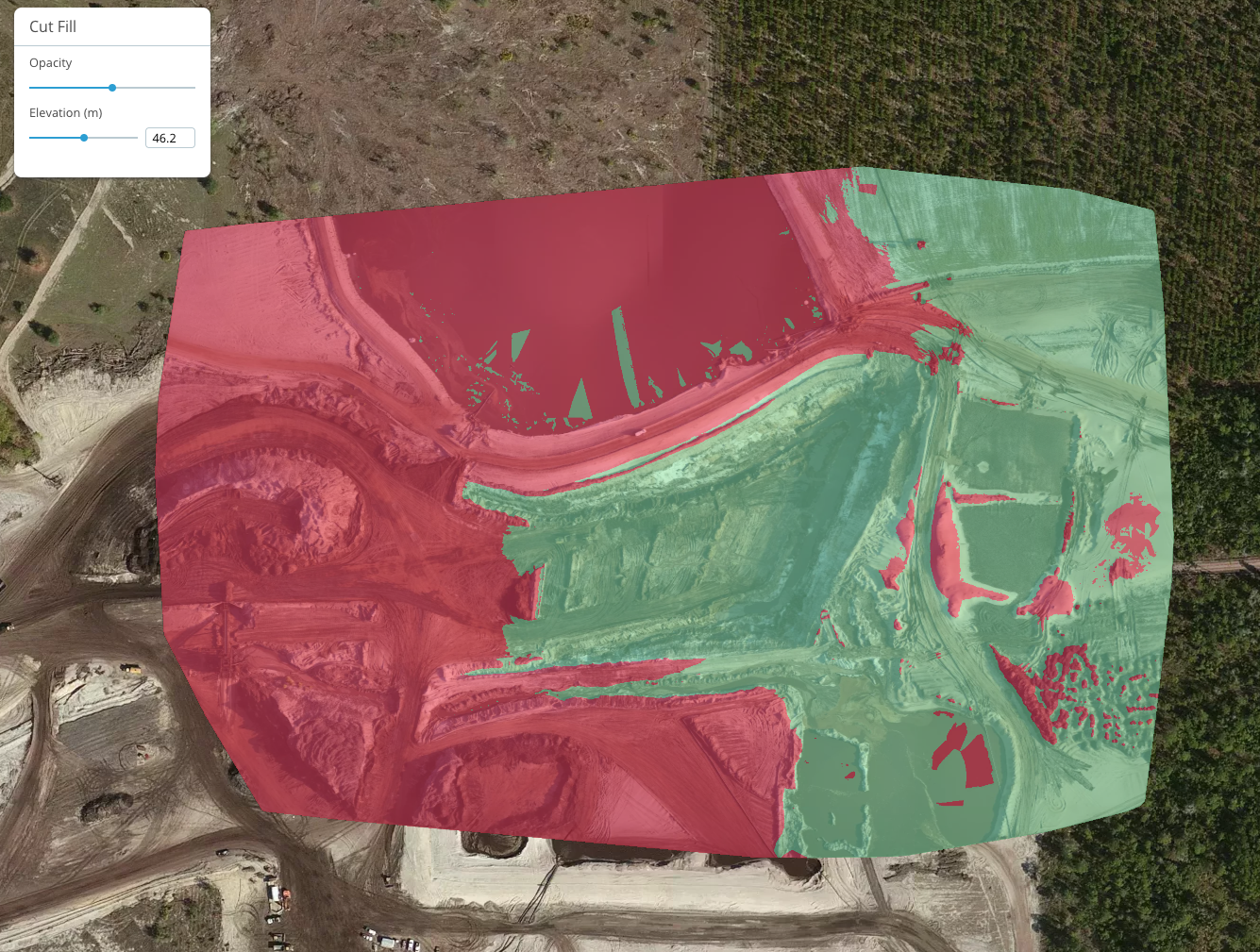

Is it helpful to try and explain the kind of difference more accurate measurements can make for professionals of all sizes and types? Or will the concept always break down because so many organizations do have different standards associated with those measurements?In 2017, I don't think the word "measurement" is specific enough anymore. A few years ago, people might have been fine to just talk about "measurement", but now I have to be very specific about what we’re actually measuring. In our case, we do a lot of volumetric analysis, and we do a lot of surface analysis, so what we're looking at are the contour lines.

The language is becoming more specific, more relevant and more industry specific. In our world, it's contours, ground control points, and digital elevation maps. In the agriculture world, for example, it's an entirely different set of metrics. There's not a lot of similarity between the markets at that level.

It’s the kind of specificity that needs to be defined for concepts like “saving time” or “saving money” as well, because that’s going to resonate much differently depending on who you're talking to. If you’re talking to a client, they have a great deal of concern about being able to save time, but if you’re talking with someone who’s paid by the hour, they typically won’t be as interested in saving time. Similarly, saving money might sound great, but the person you’re talking with might have figured out how to simply pass those costs along.

A lot of the superficial presumptions about an industry have to be tested by going out there and talking to people about the real structure, economics and pain points of that industry.

Overlay Viewer

Safety is as complicated as economics.

You and I would probably take a common sense approach to safety, so we could look at something like a DJI Spark, which is very small and intrinsically safe. That's probably true from a common sense perspective, but that's not the way the regulations are written. And I don't necessarily mean the FAA regulations, but moreso something from OSHA, or the local regulations about safety. Then you have to ask what are company policies about safety? Do you have to put up a sign that says you're flying a drone, even if it weighs 250g? Does the area have to be cleared?

If part of it is that they don't know the FAA rules about something like flying over people, those rules have to be explained and interpreted. Whether people adhere to these types of rules strictly or liberally can be a business decision, but you need to be sensitive to what the company considers safety.

It's very complex, and much more complex than the word applies to regular people, and also goes beyond describing the technology as "safer". Creating awareness around that kind of definition is a work in progress.

What kind of a difference does it make when you can talk with professionals about these kinds of details in construction, which is an industry where projects run 80% over budget and 20 months behind schedule?Construction is a massive, fragmented, geographically distributed market, and that’s part of the reason our focus on this industry over the last five years has been so important. It’s allowed us to have an understanding around core issues that result in numbers like the ones in that report.

The thing is, that “80% over budget” number isn't actually true, but not in the way you'd think. Most of the construction industry essentially underbid the project. Then, they make up their money on change orders, and changes that happen throughout the duration of the construction project. So the ultimate price might be 80% higher than the initial bid, it's actually the way that model is designed to work. It doesn't mean they're actually 80% inefficient. They might only be 10% inefficient. It just means the way the pricing psychology works is that they bid low.

So if you go in and you tell someone in construction they're 80% inefficient, they'll just tell you to get out because you don't know what you're talking about. So when you say something is inefficient, you have to ask if it's an efficiency that matters.

It’s something that must matter to enough of these professionals, as you recently mentioned that many construction teams are in evaluation mode around this technology. Outside of standardization, what are some of the factors that will play into construction teams moving out of an evaluation mode and into implementation? There are two dimensions to it.

The first dimension is just what it means to integrate this tool into their standard workflow. That's about figuring out where and when it fits into their existing process. This is the first step, and it’s really just a usual technology adoption cycle. Step two is much more interesting, because that entails changing those processes on account of this new tool. The best example of this is what you'd call the cadence of surveying.

On a construction site, you'd typically bring on a surveyor at the beginning of the project to survey the location, and possibly at the end. So it's 2-3 times at most. But what if you could survey everyday? Or every hour? All for free?

If surveys became cheap and easy, and you did more of them, then how would you manage your process differently? What would they do with that data they can gather everyday? What would real-time awareness of what's going on mean to you and your client? That's kind of a mental construct.

Distance measurement

Yes, but it’s all part of the same cycle, because the first thing construction companies want to know is whether or not something is useful in their existing business. Once they see it's useful, they're open to exploring how they can extend and expand upon that usefulness. It allows them to go through this really interesting creative reinvention of their own business, which is something only they can do. But they need to understand how the technology can go from useless to useful to basically free. Then they can start innovating.

Those innovations open up other considerations as well though, because if you’re surveying everyday, you’re going to need to involve people in that process. Can operating a drone be easy enough to push a button and it works? Or make it automated? The answer is technically yes, but regulation complicates the issue. Even with that limitation, these operators don't have to be doing that much. Maybe someday we'll be training the average construction worker to be a Part 107 operator and do nothing more than push a button because that's the way it scales.

How training can and will change for drone operators is a major topic, and you’ve previously mentioned that training is one of the challenges associated with the use of aerial scanning. Do you think training issues need to be simplified before the kind of widespread drone adoption we’ve been talking about can take place? One of the things we've seen time and time again with advanced technology is that they hit a barrier. That barrier is a trained operator.

Once upon a time, the iPhone came with a manual. And now it doesn't. That kind of thinking around a machine not needing to come with a manual, and that it should just work, is the kind of psychological pivot that traditional industries can't do, but Silicon Valley industries are supposed to do. We're seeing the same thing with drones and training.

I don't think the solution to deploying more drones is training more people. At least not beyond what they learn and know for Part 107. I think the solution is for drones to need less training. Autonomy is part of that, but it’s really about making it so using a drone doesn’t require any training at all. So that a kid could use them. So they don't have manuals, because all you need to do is open a box and push a button. That mental switch is something that the traditional airspace industry wasn't going to do because it's built around pilots and training, but it turns out to be exactly what the industry needed.

That same psychological pivot is going to be necessary as we deploy drone technology more broadly. The phrase is the "consumerization of the enterprise," and the iPhone is the best example of this concept. It used to be that advanced technology started with trained operators and businesses. Then it eventually percolated out to consumers. Now, advanced technology starts with consumers, and then comes into the enterprise via people's own choice. I suspect that consumer-driven ease of use is going to drive enterprise drone adoption as well.

Stockpile measurement

The way it's measured is not the politics, or the headlines. It's when you see movement on standardization.

It goes back to a land and expand model. Landing is great, but expanding is where the business is. So when you want to measure the success of drones transforming construction, look at the companies that standardize on them, and what that looks like across the industry.

Right now we see this with a total station. In construction, we can get very precise, millimeter-accurate positioning from this tool on a tripod that sits there, rain or shine, and can be re-positioned by someone as needed. It took 25 years to get that standard equipment, but now you see it on every site.

Drone adoption should go the same way. I hope it doesn't take 25 years, but that's how we’ll measure success, and it’s amazing to see how far we’ve come already. I didn't think we'd come this far, this fast, but we have. It's much more advanced than the military drones, and a big part of that is because the users are less advanced.

You can't move an entire industry at once. So you work with those people who are ready to make that move to evolve the industry together. That’s what we’re focused on, and it’s going to be a major factor in when and how this transition takes place.

.jpeg.small.400x400.jpg)

Comments