On December 13, 1903, the Wright brothers took to the skies in their canvas and wood machine in a flight that lasted less than three seconds and ended in an accident that caused minor damage to the structure of their Flyer.

A few days later, on December 17, the two famous brothers finally flew for almost a minute and covered 852 feet in what today we consider the beginning of aviation as we know it.

That first unsuccessful flight of December 13 might also be considered the beginning of a long and successful tradition of using aviation accidents and incidents to learn lessons and improve safety. After that mishap, Wilbur and Orville made repairs and modifications that allowed subsequent attempts to last longer and reach further.

It was the dawn of a new era in which people involved in the new industry would dedicate countless hours to thoroughly investigating every accident and every incident to improve aviation safety. These haphazard efforts lead to the Air Commerce Act of 1926 in which Congress assigned the responsibility of investigating aviation accidents to the US Department of Commerce. Later, this responsibility was transferred to the Civil Aeronautics Board's Bureau of Aviation Safety when it was created in 1940. In 1967, Congress consolidated all US transportation agencies into a new US Department of Transportation (DOT) and established the NTSB as an independent agency within the US DOT.

For a hundred years and after four generations of pilots and mechanics, traditional crewed aviation has reached a peak of operational safety perfection that is unparallel in every other mode of transportation, given the volume of traffic and the frequency of journeys.

In his fascinating book “Fate is the Hunter,” writer and pioneer pilot Ernest K. Gann describes how the second generation of pilots (from 1930 to 1950) struggled to bring passengers from Point A to Point B in unreliable aircraft, unpredictable weather, and spotty air traffic control (ATC). In the movie of the same name, but unrelated to Gann’s book, Glenn Ford acts as an accident investigator who discovered how a simple coffee spill over a cockpit console downed a commercial airliner killing everyone, except a flight attendant. This discovery led to modifications in the design of the fictional aircraft.

The last accident of a commercial airliner in the US happened in 2009 and since then over 14 billion passengers have used the system without any fatality.

In short, it took 106 years of investigating accidents and incidents to reach a level of operational safety that is considered the crown jewel in terms of transportation of passengers.

The question is, “Will it take the same amount of time to reach the same level of operational safety for uncrewed aviation?”

We do not think so. For starters we already have a fine-tuned system for the investigation of transportation accidents in all its forms, terrestrial, maritime, and aerial, so it would be very easy to add non-piloted or remotely piloted vehicles to all three branches.

There is also the issue of technical vs human and organizational factors.

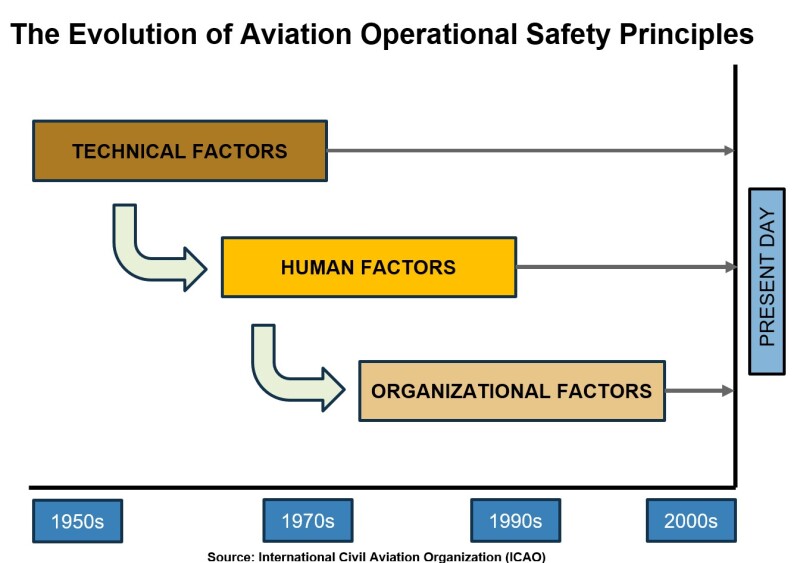

According to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the first few decades of aviation accident investigations were focused on the technical aspects of the aircraft per se, given the relatively new nature of heavier-than-air vehicles.

The following two decades were dedicated to perfecting the science of pilot training and aviator’s decision-making process, to the point when today pilots are trained and periodically re-trained to avoid human errors in the cockpit. The creation of CRM (Crew Resource Management) added a layer of safety to modern jet aviation where two pilots are needed, and a delicate ballet of responsibilities have been defined and perfected to a point where few incidents are now attributable to lack of coordination and communication within the cockpit.

Then came the third element in every human activity: The Organization. The last two decades of aviation safety were dedicated to the element that groups them all, pilots, mechanics, flight attendants, ramp operations and many others.

Lastly, we would like to mention how good we have become at weather observation and forecasting. Today, we have so many sensors and so many good micro-weather algorithms and models that having an accident because of bad weather has become almost unthinkable. It still happens, of course, but with every new occurrence we add a new safety measure for every new lesson, to reduce the number of future accidents.

For all these reasons, uncrewed aviation has an advantage of a few decades with respect to the crewed aviation of the 1930’s or 1970’s. In our opinion, it will take just a few years for aircraft, pilots, mechanics and organizations to fine tune their drone and air taxis’ operations to the point where uncrewed aviation will be able to safely and fully integrate into the national airspace with its piloted counterpart.

Comments