Now that we have examined in detail the different Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) operating modes, including Part 121 for scheduled flights, Part 135 for unscheduled charter flights, Part 91 for personal use, and Part 137 for agricultural spraying, amongst many others, it is time to separate their different levels of safety records.

Commercial airliners operating under Part 121 have had just two fatal accidents in 15 years, resulting in the death of two passengers since 2009. In this period the airline industry has safely transported over 15 billion passengers across the country. Unfortunately, the reality of safety under Part 91 and Part 135 is very different.

The largest general aviation membership organization in the US, Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), releases an annual report on the safety of the industry that is always helpful to understand the reality of Part 91 and Part 135. A few weeks ago, the AOPA Air Safety Institute released the 34th Richard G. McSpadden Report (formerly the Joseph T. Nall Report), which presents users with near real-time accident analysis updated on a rolling 30-day cycle.

The accident data used in the report is from 2008 to 2022, which is the last year the NTSB has officially released complete records. Please note that the NTSB takes approximately two years to issue a probable cause statement, so only preliminary data is available for 2023 and 2024.

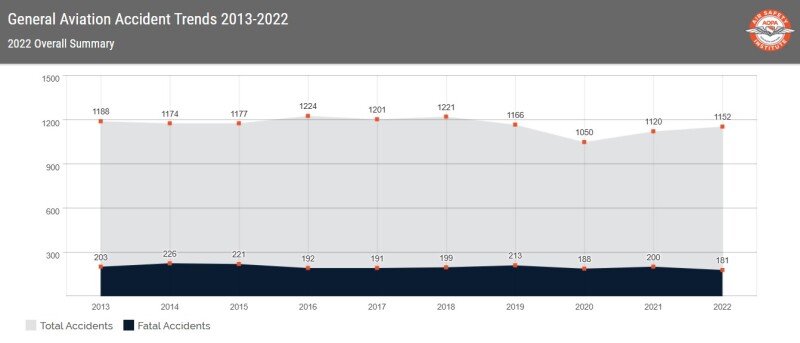

The picture is not as rosy as with Part 121. In this case, most, if not all, these accidents occurred while operating under Part 91 or Part 135. In 2022, there were 1,152 general aviation accidents, 181 of which were fatal. This was an increase of 32 accidents in comparison with 2021, and 102 more than in 2020, the lowest number of accidents in over a decade, perhaps attributable to the COVID-19 restrictions.

The average for the decade 2013 to 2022 is 1,167 accidents per year, of which 210 were fatal.

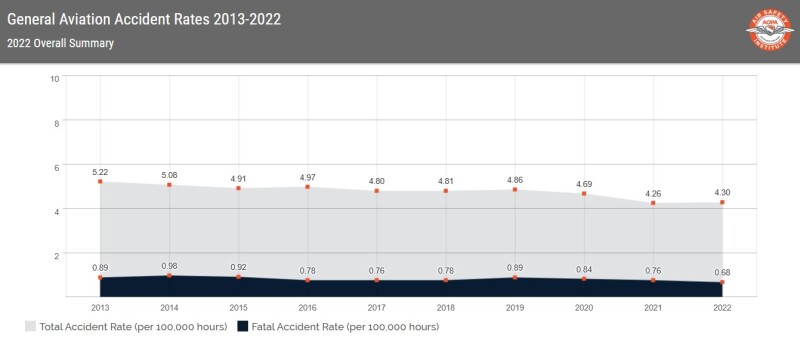

A better way to look at this data, if we are planning to use it as a warning sign for an uncrewed aviation safety forecast, is to look at it in terms of accidents per hour flown. The AOPA Air Safety Institute uses the ratio of accidents per 100,000 hours flown, and this way of looking at the trend tells us more about safety improvements.

Using the data from 2013 to 2022, there were an average of 4.8 accidents per each 100,000 hours flown by general aviation aircraft under Part 91, with the last two years, 2021 and 2022, being the lowest of the entire decade. This seems to indicate an important increase in safety.

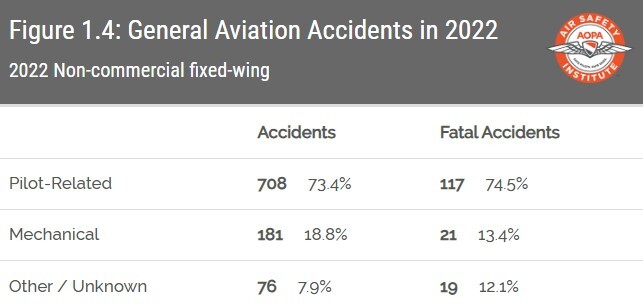

It is also important to analyze the reasons for these accidents. For this, the AOPA safety report is valuable in the sense that divides the various occurrences in the following three categories: pilot error, mechanical failure, and unknown.

As we can see, almost three quarters of all general aviation accidents are attributable to pilot error, with only 13.4% due to mechanical failure and 12.1% to other causes.

It will be important for the uncrewed aviation industry to analyze what happens when we apply these statistics to aircraft that do not have a pilot on board and will be less subject to weather issues (due to the altitudes that will be used in uncrewed aviation), and the relatively short distances of the flights.

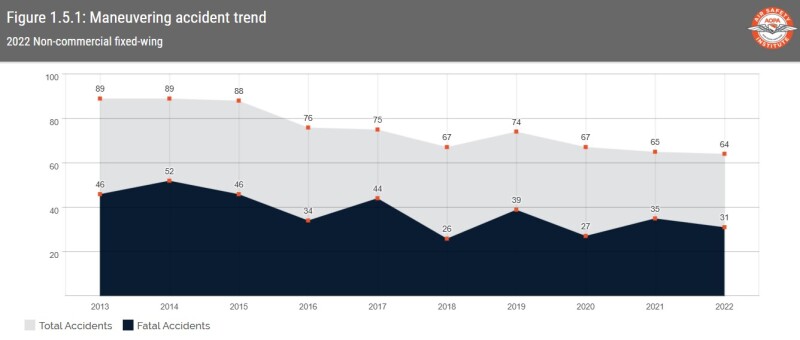

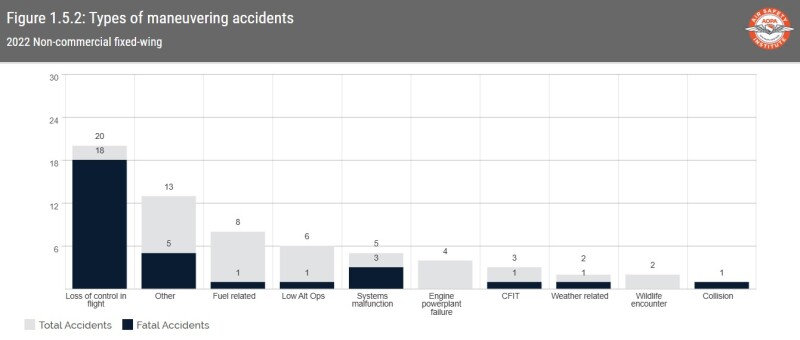

Due to the large number of accidents that are related to pilot error, it will be useful to analyze what specific areas are particularly vulnerable when it comes to pilots. The overwhelming winner in terms of most deadly accident is “Loss of Control in Flight,” which constitutes a third of all accidents but at the same time accounts for 60% of all fatalities. Losing control of the aircraft is obviously very difficult to survive.

This statistic is very important to the uncrewed aviation industry because it emphasizes the importance of the pilot in general aviation, and it will be a warning sign in terms of pilot certifications and recurrence.

In Part 121, with its perfect safety record over 15 years, pilots are required to attend recurring training once or twice a year in a simulator and there are always two pilots on board and lots of automation and redundancy. This is not the case with Part 91 where most flights are single pilot sorties and there is no ground support or operational safety standards.

It is up to the companies now shaping the future of uncrewed aviation if they are going to follow the path of Part 121 with all its stringent requirements, both human and mechanical, or go the route of Part 91 with its more relaxed safety standards.

We hope, for the sake of advancement in the use of non-piloted aircraft, that the industry learns the lessons from general aviation and decides to adopt strict operational standards and ethics codes that will allow this new industry to flourish in safe harmony and integration with its crewed counterparts.

Comments