We’ve attempted to lay out what people need to know about counter-drone / anti-drone technology, but it’s a segment of the overall drone industry that continues to evolve at a rapid pace. Many organizations are attempting to tailor a counter-drone solution to fit specific security needs, but what are some of the logistics associated with that approach? Which companies can support it, and what are the regulatory limitations with that kind of system?

The Counter-Drone Market Report from the team at DRONEII explores these specific details for the benefit of anyone attempting to assess and answer these questions. Their report lays out what the counter-drone industry actually looks like, highlights which companies have relevant products in it, where counter-drone regulations currently stand across the world and much more.

To get a better sense of the insights that are available in the full report, we connected with Kay Wackwitz, CEO of DRONEII. We’ve talked to him about everything that’s impacting the drone market from disruption to partnerships to how information gathered via drone can impact decisions at scale, but we used this opportunity to focus on how counter-drone solutions are going to make a difference in 2020.

Jeremiah Karpowicz: Your report mentions that counter-drone companies offer detection systems, interdiction systems or a combination of the two. However, the technical and legal details associated with detection versus interdiction are vastly different, aren’t they?

Yes, they are. Drone interdiction typically lies in the hands of governmental entities. A drone in the air is considered an aircraft and there are laws that prohibit any interference with flying aircrafts. In fact, there are regulations in place prohibiting not just the kinetic interdiction methods (projectiles, laser, nets), but also the non-kinetic methods (jamming, spoofing).

If counter-drone solutions can be simplified into those two options, what would you say are some of the notable differences between the 249 counter-drone companies and 575 solutions that are called out in your report?

It’s the sophistication of the solutions. Counter-drone solutions can either be very simple or very complex – depending on the criticality of the infrastructure they are meant to protect. This can range from a simple radio frequency (RF) scanner to a multi-sensor solution (consisting of a combination of optical, acoustical, RF, and/or radar tools) for the detection of a drone. Same accounts for the interdiction solutions.

Your report details how much money has been spent on counter-drone solutions for nearly a decade, but what can you say about how this conversation has changed over that period of time?

From my perspective, the counter-drone industry is finally getting the awareness it deserves – even though the reason for it was a very unfortunate unlawful interference with air traffic which had negative implications on people’s lives. Gatwick 2018 was a wakeup call by showing the impact of a small drone on an international airport – luckily without an accident or anyone getting hurt.

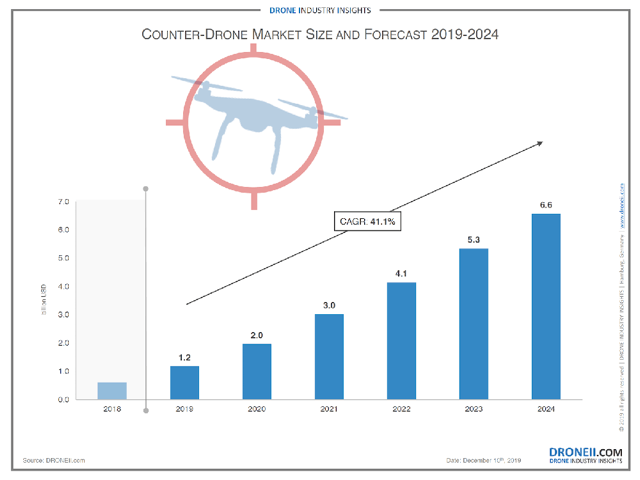

Looking at the growth of the counter-drone market from 2019 to 2024 makes it seem as though the counter-drone market could be bigger than the drone market itself, or perhaps develop quicker. Would you say that’s accurate?

In the coming years, it is not growing bigger but it will certainly grow faster. The commercial drone market is expected to grow to 43.1 billion USD in 2024 at a CAGR of 20.5%. Meanwhile, our report shows that the counter-drone market is expected to grow to 6.6 billion USD in 2024 at 41.1%.

When it comes to the adoption of a counter-drone solution, how much of that decision should be driven by the regulatory landscape for a given company/operation?

The impact for some counter-drone technologies is not yet fully assessed, especially the collateral damage they might cause in densely populated areas. Drone detection systems scan the environment for signs of drones. This can be an acoustic signature, a radio frequency, a radar echo, etc. All of this is perfectly legal when in line with the federal telecommunication authorities.

As these systems advance and with better knowledge about their impact on thirds, I’m confident that governmental bodies will start to loosen regulations on interdiction methods e.g. opening up some of these options to private security firms with special training.

Additionally, the use of active interdiction methods must be strictly regulated – in the end, these are weapons pointed at an object in the air. The collateral damage caused e.g. by jammer systems or fired projectiles that missed the target is extremely hard to assess – especially in urban areas. Don’t get me wrong – there are critical infrastructures and circumstances that require this kind of “hard kill” option to exist.

However, there is a lot you can do to protect you property/company from drones without any direct interaction. The first thing you need is the awareness of the presence of a drone, it’s location, heading and (if possible) the identification. This alone enables you to trigger all sorts of reactive measures. There can be a “drone alert” to notify your staff to e.g. close the window blinds to prevent the drone from spying or to bring the new prototype car you’re testing off the street. In case of a cyber-attack by drone, you can shut Wi-Fi and search the premises for Wi-Fi-sniffers. The list of possibilities is long and all of them are perfectly legal and require no governmental approval.

What were some of the most notable insights from the case studies that are fully documented in your report?

The most notable insight is the diversity of protection scenarios. We compared airports, prisons, events and industrial facilities and saw, that they all call for very individual protection scenarios. For these four infrastructures, we checked the threat level (safety and financial), the interdiction necessity and the implementation complexity. We discovered that some of these infrastructures require very sophisticated multi-sensor, multi-effector solutions while others just need a simple detection device. This means that the price range of counter-drone security ranges from a few thousand dollars to a few million dollars.

Ultimately, what sort of person or company is going to get the most out of your report? How do you foresee it impacting decisions that need to be made in 2020?

First, we want to put drone things into perspective and take the hype, just as the paranoia out of the conversation. This report helps counter-drone system manufacturers just as governmental bodies and companies who want to better understand the threats and opportunities to mitigate those.

Counter-drone system manufacturers can use it to build up competitive intelligence, to find new target markets, better understand national regulations and to use the market size/forecast to build business plans or pitch decks for investors.

Governments, companies or private individuals can use the report to benchmark different solutions, to better understand the market landscape, their players and to learn more about how to thoroughly protect their individual infrastructure.

What’s one thing you want anyone to know about how this technology is going to make an impact?

As mentioned before, the threat is real and it’s time to better be safe than sorry. The one important thing to know is, that there is much more possible than one might think to protect yourself against drone threats. The governmental hurdles seem to be very high but - depending on the infrastructure you want to protect - the solution can be very simple.

Comments