In our fascination with finding alternative power sources and any other scheme that would extend flying time for commercial unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) operations, we come across ingenious alternatives all the time. From hybrid power plants to fuselages that act as batteries, many companies are coming up with original arrangements that normally involve improvements over existing technologies and others that are utterly original.

One great example is the Raybird-3, designed and manufactured by Skyeton a Ukranian company that has recently completed a full cycle of trials of their revolutionary platform and is now transitioning to full production and further research and development in Canada. We reached out to Amir Ashrafi, General Manager of Canadian Operations at Skyeton, and he elaborated on the technology.

One great example is the Raybird-3, designed and manufactured by Skyeton a Ukranian company that has recently completed a full cycle of trials of their revolutionary platform and is now transitioning to full production and further research and development in Canada. We reached out to Amir Ashrafi, General Manager of Canadian Operations at Skyeton, and he elaborated on the technology.

“In designing the Raybird-3 technology, Skyeton focused on three key aspects: The airframe and its capabilities, the maximum possible degree of flight automation from takeoff to landing, and the reliability of operations with durability in mind.” Amir said.

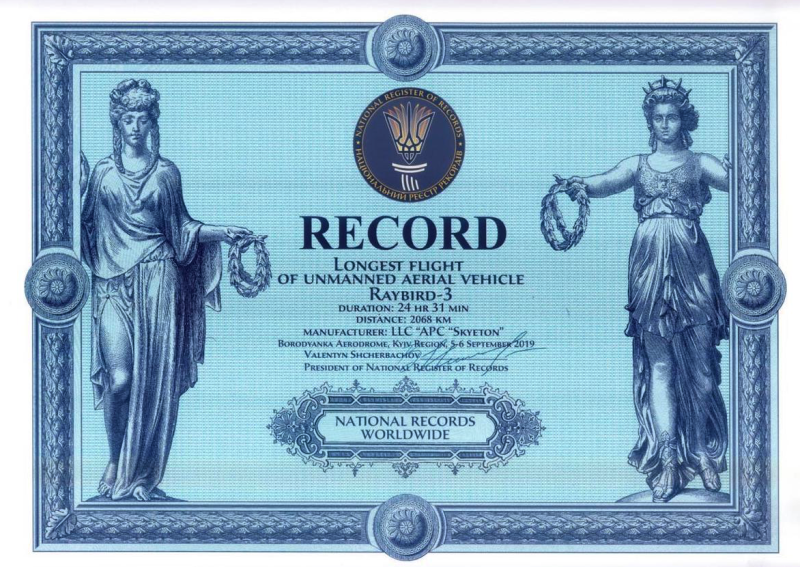

In September 2019, Skyeton announced it had broken the Ukrainian record for longest flight for a small UAV. A version of the Raybird-3 weighing 46 lbs and fully equipped, stayed airborne for over 24.5 hours.

“Designed for professional use, the Raybird-3 UAV has a fuel injection engine and an in-air endurance of up to 32 hours,” Amir explained. “It can fly missions while transmitting streaming live video over a radius of 120 kilometers. The maximum operational ceiling is 10,000 feet. In its current configuration, the Raybird-3 UAS consists of three UAS with mission-specific payloads, a foldable catapult launcher, a ground control station (GCS), aerials and other support equipment, including spare parts and fixings, all transportable in four ruggedized containers weighing collectively about 200 kilograms.”

The Raybird-3 can be transformed from the container to operational flight by two people within 15 to 20 minutes and does not require any screwdrivers, wrenches, or other similar tools to assemble or disassemble for storing.

The Raybird-3 is launched by a mechanical catapult and the landing is assisted by a parachute and a reusable, electrically pumped airbag to cushion the impact on the airframe. While approaching the landing site, the aircraft ‘flips on its back’ to minimize the risk of mechanical damage to the payload equipment.

It is powered by a carbureted engine, developing 3.5 horsepower, which, admittedly, on several occasions proved excessive for some of the routine missions tested. An electronic fuel injected engine is optional. An onboard starter/generator provides electric power to the mission and payload equipment and enables remote engine on/off control while in flight. Critical systems such as flight control surfaces and servos are duplicated to improve reliability and safety of operation.

“Since the flight is highly automated from takeoff through to touchdown, the human operator’s duties can be focused on managing payload equipment. Modular architecture allows for payloads of up to 7 kg, ranging from a snapshot camera to a gyro-stabilized camera laser rangefinder, or synthesized aperture radar mounted in a stabilized gimbal. Payload packages can alternatively include radio relays and electronic warfare/countermeasure equipment.” Amir stated.

The gimbal can lock on and automatically track up to five objects of interest, moving or static, simultaneously, and can automatically locate objects within its field of view. The aircraft can be optionally equipped with an Epsilon 140Z gimbal, integrating an optically zoomed IR camera with a laser designator/rangefinder.

“I also want to add that our ADS-B two-way capability allows aircraft from 500’ to 80,000’ to be aware of our aircraft, therefore allowing for collision avoidance and enhanced safety,” pointed out Amir. “Also, in terms of productivity, we can scan an area of 250,000 acres in 10 to 12 hours.”

Skyeton believes that the less a user intervenes in controlling a UAS, the better. This approach, according to Amir, is based on statistics gathered during Raybird-3’s testing and operation. Any technology that contributes to longer flying time is welcome and enhances the possibility of new missions and new applications for commercial UAVs.

Comments