“When human-to-human contact is the problem, send in the robots”

Social distancing has become the new normal as the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps the globe. The U.S. is not immune, reporting more than 30,000 confirmed (and, frankly, underreported) cases to date. When human-to-human contact is the problem, send in the robots.

In the current crisis, UAS regulations seem to constrain maximum UAS employment for the good of society; yet on a daily basis, other significant policies continue to evolve in response to the unprecedented situation in which we all find ourselves. Why would we not revisit UAS policies and regulations to enable remote package deliveries (food, medicines), police first response, and communications, at a minimum, on an emergency temporary basis? (Spoiler alert: there is actually a way to do this in an expedited manner in emergencies!)

Drones for Good

Other countries have embraced drone technology, using them in novel and useful ways to combat the Coronavirus. China, for example, has employed drones to enforce quarantine restrictions, aid in street and hospital disinfection, and deliver construction, medical and food supplies. They are also using drones to remotely communicate. Equipped with megaphone payloads, authorities have been telling people to go back inside their homes.

Several countries in Europe which have imposed stop-movement orders have followed suit. On March 15, Spain began to employ its own version of megaphone drones to aid in quarantine enforcement. Four days later, France followed suit.

Drones also continue to be used across the globe for media purposes, showing empty streets in Italy, rapid hospital construction in Russia and even relating happy stories, such as a drone flower delivery to a very surprised mom in Lebanon on Mother’s Day.

In the U.S, drones are also being used, but not as extensively. The Financial Times just reported that in California, the Chula Vista Police Department just purchased two drones equipped with loudspeakers. Grant Guillott, Esq., Founder of the UAS Practice Group & Partner, Adams & Reese LLP, authored a recent article discussing how the U.S. drone industry is contributing to the COVID-19 fight. Some uses include: creating virtual meetings out of site visits (Ken Hanes, AGL Drones Services); inspections of remote facilities, media capture, package delivery, safety management, security monitoring, situation awareness, and remote temperature readings (Tom Walker, DroneUp); COVID19 Task Force for lessons learned (Charles Werner, DRONERESPONDERS); and airborne awareness/media coverage (Chris Todd, Airborne International Response Team or AIRT).

In Grant’s recent podcast, “Can Drones Make a Difference During the COVID-19 Pandemic?” industry leaders, such as Ken Stewart (AiRXOS), Charles Werner (Drone Responders) and Chris Todd (AIRT) discussed what drones could be used for right now. As an example, Ken posited that drone delivery and retrieval of COVID-19 test kits to and from the cruise ship that was stuck off of the California coast would have been cheaper, safer and more effective than the Blackhawk helicopter that was actually used. All essentially agreed that that the current regulatory environment limits UAS employment and that we should use this crisis as a way to gather lessons learned to inform future planning.

As a military vet, and former operational law attorney, far be it from me to disagree with boots-on-the-ground operators or with the concept that planning is critical to any effort. I don’t here. My two cents: the operations required in these times have already been occurring for years.

Novel but Not New

Since 2016, Part 107 has enabled the operation of small UAS (sUAS—weighing less than 55 lbs.) without requiring airworthiness certification. However, to operate over persons, at night, above an altitude of 400 feet, or beyond visual line-of-sight (BVLOS), requires a waiver. Large UAS operations and any other sUAS ops outside of 107’s parameters require either an airworthiness certification from the FAA or an exemption.

Even before Part 107 was enacted, in 2013 the FAA selected six public entities to be designated as test sites, and added another such site in 2016: North Dakota Department of Commerce, State of Nevada, New Mexico State University, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Texas A&M University at Corpus Christi, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University, Griffiss International Airport (New York) and New Mexico State University. Pursuant to test site authorities, industrial partners have been conducting testing and evaluation (T&E) as well as research and development (R&D). Collectively, over the past five years these sites have facilitated more than 15,000 UAS flight tests, supporting R&D across critical areas, such as BVLOS flight, command and control links and equipment, UAS-based and ground-based detect and avoid, cybersecurity software systems and the ability to carry loads of varying weights, to name a few.

Important to the current situation, these test sites have engaged in significant hazard and risk mitigation T&E, building safety cases that enabled FAA approvals to conduct complex UAS operations. State Farm Insurance worked with the Virginia test site for more than a year to build a safety case proving they could safely operate sUAS BVLOS and over people. This risk mitigation testing “entailed dozens of experiments, including how to address the risk of an UAS abruptly losing power.” Based on this, the FAA granted approval for the company to fly its fleet of UAS over people and BVLOS in sparsely populated areas.

This T&E and supporting R&D has validated a wide variety of other drone use cases. For example, disaster recovery UAS were used during and after Hurricanes Dorian, Harvey, and Florence in 2019, 2017 and 2018, for search and rescue missions, damage assessments and media coverage.

Layer on top of this R&D, the Department of Transportation’s (DOT)’s UAS Integration Pilot Program (IPP), consisting of 10 project teams—including Alaska, North Dakota, and Virginia test sites—that evaluate different UAS operational concepts in specific communities. According to the DOT, “the IPP is an opportunity for state, local, and tribal government agencies to partner with private sector entities, such as UAS operators or manufacturers, to, among other things, accelerate the approval of operations that currently require case-by-case authorizations.”

In May 2018, the FAA selected the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) as one of 10 IPP participants. NCDOT, Division of Aviation, have been using drones primarily to deliver life-saving medical supplies and to run food delivery services. NCDOT and its partners began their first flights in the Raleigh area in early fall 2018, collaborating with WakeMed. By early 2019, UPS, in partnership with the Swiss company Matternet, had launched a healthcare delivery service at WakeMed using the Matternet M2 drone logistics system. Consisting of the Matternet M2 drone and the Matternet Cloud Platform, the system is capable of transporting packages of up to 5 lbs. over distances of up to 12.5 miles in operations BVLOS and over people. By October 2019, they successfully completed more than 1,000 deliveries. As a result, the FAA approved the first “drone airline” under Part 135 Standard certification (air carrier certificate), permitting UPS to rapidly scale drone delivery hospital operations on a national scale.

Additionally, Wing, a Google company, again in affiliation with an IPP, was the first company to receive Part 135 approval, in April 2019. These are but a few of the many success stories in the FAA test site and IPP arenas, and probably two of the few very open-to-the public ones.

The lack of transparency and analysis relating to work performed at test sites and IPPs has been duly noted. In January 2020, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), after conducting a performance audit on the FAA from July 2018 to January 2020, issued a report, GAO-20-9, UNMANNED AIRCRAFT SYSTEMS FAA - Could Better Leverage Test Site Program to Advance Drone Integration. The report concluded that while the FAA collects data from test sites, “it has not fully leveraged the data or the program to advance UAS integration.” Specifically, the GAO found that the FAA had not determined which test site data could inform the agency’s risk assessments for UAS (which would be relevant to Part 135 delivery certs or other complex UAS operations). The GAO recommended that the FAA:

- develop a plan for analyzing currently collected UAS test site data to determine how they could be used to advance UAS integration, and whether the collection of any additional test site data, within the agency’s authority to request, could be useful for informing integration and

- publicly share more information on how the test site program informs integration while continuing to protect information deemed proprietary. This information could be shared, for example, on the agency’s UAS Test Sites website.

The Secret Sauce

“Those who have the appropriate approvals, need to keep using them for good…. Those who have UAS capabilities they want to unleash, harness the power of information and make your case now.”

While the GAO has recommended data analysis for the test site/IPP R&D, this will probably take years and resources that are likely not readily available to the FAA. The proof is in the pudding, though, and there is pudding right now in the form of Part 135 approvals and Part 107 waivers or exceptions to policy (ETPs), as well as all of the risk analysis, R&D, testing that undergirds them. Let’s use this information to enable ops as we tick off days in isolation.

Those who have the appropriate approvals need to keep using them for good. Folks like Wing, Matternet and UPS should make the much-needed deliveries and continue proving to all that drones are critical tools that can be used for societal benefits.

Those who have UAS capabilities they want to unleash, harness the power of information and make your case now. The secret sauce is out there, folks. It just takes some digging. For example, there is a Special Government Interest (SGI) request that can be used in emergencies. It is an expedited approval process applicable to first responders and “other organizations” (not defined, by the way) responding to natural disasters or other emergency situations that already have an existing Part 107 current certificate or Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA) for operations including (*but possibly not limited to):

- Firefighting

- Search and Rescue

- Law Enforcement

- Utility or Other Critical Infrastructure Restoration

- Incident Awareness and Analysis

- Damage Assessments Supporting Disaster Recovery Related Insurance Claims

- Media Coverage Providing Crucial Information to the Public

For more, see: https://www.faa.gov/uas/advanced_operations/emergency_situations/

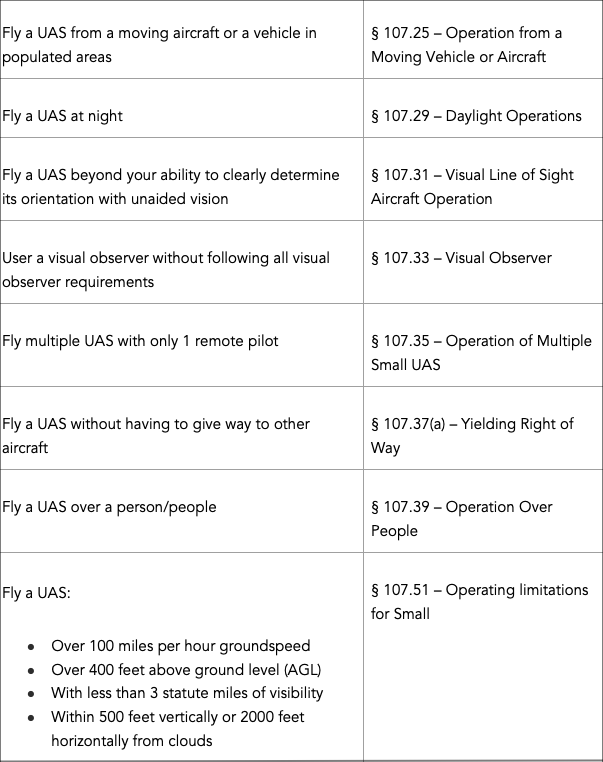

This process appears to apply to all complex operations, including under both Parts 107 and 135. As a refresh on Part 107 waivers, here’s the FAA’s handy dandy chart:

“Under the law, the FAA has the authority to issue temporary, emergency rules, without public notice or comment for ‘good cause.’ Concern for public safety in emergencies is legally such a cause.”

To date, the FAA has issued 3,983 such waivers, 49 for BVLOS alone. Part 107 waiver certificates can be found here. Scanning a few of these gives you a good idea of what the FAA is expecting in a waiver package. The FAA has also posted trend analyses to illustrate good versus bad packages for both BVLOS and operations over people (OOP) (see, e.g., here).

As for the FAA’s part, one would think that rapidly moving out on these waiver, ETP and expected approval packages would be the immediate mission to get us through the current times.

Better yet: The FAA has the authority to issue temporary, emergency rules, without public notice or comment and without the 30-day waiting period, under the Administrative Procedures Act’s “good cause” exception. 5 U.S.C. § 553(b)(3)(B). (Yes, I kind of saved the best part for last).

This allows Agencies to forgo the normal requirements of notice and comment rulemaking when it is “impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest.” Concern for public safety in emergencies is one of those grounds. Thus, temporary modifications to Part 107 limitations to allow night operations, OOP, BVLOS in already established use cases and with validated risk parameters could actually occur. If there was ever a time to invoke this authority to allow these ops, it’s now.

Woulda, Coulda, Shoulda?

“In the current crisis, UAS regulations seem to constrain maximum UAS employment for the good of society. Let’s not posture ourselves to look upon our actions during this time with regret. This, indeed, could be the finest hour for the drone industry as whole…”

Extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures. As Sir Winston Churchill once said, “To each there comes in their lifetime a special moment when they are figuratively tapped on the shoulder and offered the chance to do a very special thing, unique to them and fitted to their talents. What a tragedy if that moment finds them unprepared or unqualified for that which could have been their finest hour.” Let’s not posture ourselves to look upon our actions during this time with regret. This, indeed, could be the finest hour for the drone industry as a whole, both those who operate in it and those who govern it. Lessons learned from the test sites, IPPs, and the operations conducted during this pandemic will propel us into the future. Embrace the moment. Innovate and prosper!

Comments