The phone rang in the office of the Canary Islands’ Government Emergency Response, and it was not good news. It was September 19, 2021, and the voice on the other end of the line said, “There’s a new volcanic eruption in La Palma, and it looks bad. Get ready.”

The volcanic eruption at the Cumbre Vieja region of la Palma Island would eventually become one of the worst in the convoluted geological history of the Canary Islands’ archipelago. Formed by eight individual islands, the Canaries, as they are commonly known, are a beautiful mixture of black sand beaches and rich agricultural land that form a tropical paradise west of the African continent but belonging politically to Spain.

A coordinated and well-oiled emergency response machine was put into motion. In a few hours, thousands of public servants along with government and non-governmental (NGOs) organizations descended on the small island of La Palma to begin evacuations and prepare the scene for a recovery that was uncertain in terms of time and scope. Dozens of international news organizations and scientists also arrived in La Palma for a view of one of nature’s most powerful demonstrations.

And this is where the story becomes especially relevant to the drone industry in general while also highlighting the inevitable merging of crewed and uncrewed aviation.

One of the heroes of our story, Xandra Renedo, is a young forest engineer who has specialized in forest fires and whose job for the Government of the Canaries is to act as air traffic controller for crewed aerial operations during fire emergencies. A few days after the first eruption, Xandra received a call to report to La Palma as an air traffic controller.

The government of the Canary Islands has a dedicated UAS team led by Enrique Sanchez Déniz, who took command of uncrewed operations at the volcanic event. While Xandra is from another government agency, Enrique nonetheless sought her help with air traffic control and to put order to the hundreds of organizations that wanted to fly over the active volcano.

Two days before the eruption, Enrique and one of the pilots in his roster, Juana M. Medina, were at the volcano with a team from the Spanish Geology and Mines Institute performing photogrammetry flights to gauge the degree of deformation that was being caused by the constant tremors registered in seismographs all over the world. They were performing a flight the moment the volcano erupted on 09/19 and were caught in the initial deluge of lava and ashes. Thankfully, they were upstream from the deadly flow, with a vantage point over the developing disaster.

We had the opportunity to meet Enrique, Xandra, and Juana at a drone conference in Spain, and we spent some time listening to their stories, which covered a range of topics and drone logistics. The stories left us wondering how does an air traffic controller whose expertise is directing crewed aviation responses from a helicopter respond to an order to report to an emergency where crewed aviation is banned, and what does it mean to enable coordination with such a diverse set of people and departments?

Answers to these questions showcase where crewed and uncrewed aviation is both merging and evolving. Xandra had the knowledge and the expertise to direct the complex aerial response to forest fires from the vantage point of a helicopter hovering over the affected area, but without a mandate to order or force pilots to do anything specific, all she could do was direct traffic and recommend points for dropping fire retardants.

She quickly understood the magnitude of the job at hand and the drastic differences between the options that crewed and uncrewed aircraft enabled in the situation.

“Before that day, I had never seen a drone in my life!” Xandra said laughing. “My experience was directing huge, piloted aircraft dumping fire retardant over very specific areas in an attempt to control a brush fire. This was entirely different; this was sitting in an office communicating via phone with sometimes tens of operators at the same time, all desperate to receive authorization to fly over a volcano!”

The Canaries’ government quickly set up an improvised authorization system based on WhatsApp’s Groups, a popular and widely used encrypted, messaging app. Drone operators from around the world descended on La Palma with the intention of capturing a one in a lifetime event for posterity. That created challenges on multiple level.

“The biggest problem that we had is that there were missions that were a priority, such as scientific flights and constant monitoring for evacuation purposes,” Xandra explained. “There were constant new openings in the volcano and new and unexpected lava flows threatened populated areas, so we had to give priority to those flights that were reporting new developments.”

The Cumbre Vieja volcano is not really one open caldera. Rather, it is a long mountain top ridge that was constantly erupting in several areas on both sides of the mountain and sending lava in different directions. Job number one for Xandra and her team was to keep the government drones flying and reporting new openings, as well as setting up in motion evacuation procedures.

“My phone was constantly ringing with new WhatsApp notifications about flight authorizations and messages from pilots desperate to get to the air to photograph and document the continuous eruptions,” Xandra said. “It was a delicate balance between the availability of the airspace around the volcano and the good will and behavior of the multiple operators flying in close proximity to each without any possible way for us to supervise or control.”

The first thing that happens when a volcano erupts is that crewed aviation is grounded for miles—sometimes hundreds of miles—around it. This is because volcanic ash is abrasive, and aviation engines can disintegrate and explode after a few minutes of exposure.

“In my experience with forest fires, I normally get deployed to a helicopter hovering over the area and coordinating with pilots and ground crews the best way to deploy the resources to combat and hopefully extinguish the flames,” Xandra stated. “But in this case, there was nothing to combat! You don’t fight a volcano, you run from it. We were in charge of a fleet of unpiloted aircraft and this time, we did have control over their movements and their authorization to fly. It was an exercise in coordination and cooperation. Every person operating over the volcano knew that lives were at stake and behaved like a community.”

“It was incredible, flying crews from all over the world were applying for airspace authorizations, and we had to review, approve, or reject and then manage the congestion in the area from an office far away, on the other side of the island,” Xandra reflected. “At the end, it all worked out, but to tell you the truth it was a baptism of fire, no pun intended! In total, I believe we approved over 3,500 operations, each one consisting of many flights for battery changes and repositions over a period of three months.”

While Xandra was directing traffic around the volcano, Enrique Sanchez Déniz and his team of pilots were flying official missions under her supervision.

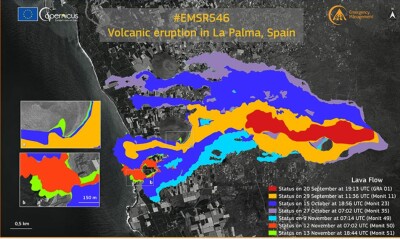

“Every day, we first flew photogrammetry missions to determine the changes in the shape of the caldera and the surrounding areas,” Enrique said. “Then we flew photographic and scientific sorties in which we recorded various aspects of the eruption, including thermographic analysis of each lava flow and made a photographic record of the damage to property.”

There are hundreds of great videos about what happened in La Palma from September to December 2021 but this compilation by Rafa Ocon shows the harsh flying conditions that were encountered by pilots and aircraft alike during the event. The video also features interviews with Xandra and Enrique that present a unique, behind-the-scenes look at what happened during those fateful three months.

What we saw during La Palma volcanic eruption in 2021 was a complete ban of crewed aviation and a replacement by uncrewed aviation being directed by a seasoned traditional air traffic controller. This smooth transition might have not been possible five years ago. This emergency scenario where various governmental and non-governmental agencies, scientific institutions, and news outlets from around the world converged in a small island to be masterfully choreographed to monitor and report to the world in real time might be the perfect baseline to gauge the progress we are capable of five years from now.

This is one more piece in the emerging picture that we are all aviators, and we will eventually live and work in a world where piloted and non-piloted aircraft will share controlled airspace.

Comments