“What about that one?” asks Blake Resnick, founder and CEO of BRINC Drones, as he points to a drone that’s folded up and off to the side. “Does that one have it?”

We’re at BRINC headquarters in the Fremont neighborhood of Seattle, Washington, and Resnick and his team are giving me a sneak peek of the Responder drone and Responder Station charging nest that will be launched in a few days. The production floor is a flurry of activity because of that, with literal pieces and parts going in various places as we speak. That’s undoubtedly why the siren, which is one of the key features of Responder, isn’t currently set up on the drone that’s in front of us.

One of the engineers checks the other Responder drone that Resnick had pointed to, but then slowly shakes his head. They’re in the middle of some tests so that siren feature isn’t up and going with the ones at this station. I assure him it’s totally fine, and just the visuals alone are enough to convey a sense of this drone being a tool that specifically makes sense for emergency response. It looks (and undoubtedly sounds) like something the general public will instantly recognize as being connected to police or as part of a first responder (DFR) program.

Resnick quickly nods in agreement and mentions how these sorts of visuals and features have been a key consideration. They’re connected to BRINC’s focus on the public safety sector and only the public safety sector. That sense of purpose is evident as we watch Responder take to the air with those lights flashing. Still, Resnick mentions that hearing the siren brings it all together.

“It just really gives you a sense of what’s possible for these drones to revolutionize the public safety landscape,” Resnick says with a slight sense of disappointment that belies his passion for the technology. He wants me and everyone else in this public safety landscape to understand not only what’s possible with these solutions, but with what can be done with them right now. With sirens being just a small part of it.

That passion as well as a focus on what can be done with these solutions right now are two essential elements of this visit, but also for BRINC and to the entire drone industry.

Dominating a niche market

If you’re not familiar with Resnick’s backstory, it’s a notable one for several reasons. A Las Vegas native, the 2017 shooting that took place on the Las Vegas Strip got him thinking and asking about how public safety technology could make a difference in these exact situations. Those questions would eventually lead him to a Thiel Fellowship that enabled him to found BRINC in 2020.

Publications that range from Business Insider to The Seattle Times to Bloomberg have all detailed this history, with some especially amusing details about his recent funding journey revealed on the GeekWire podcast, as well as how his parents tried to bribe him to not drop out of Northwestern…to no avail. All of which is to say you can find plenty of sources that detail the past of the company, making it that much more important to focus on the present. However, the Thiel Fellowship has an important connection to both.

Created by billionaire Peter Thiel, the Thiel Fellowship provided Resnick with the funding to get BRINC off the ground, but the impact of it was about more than funding. Thiel has written about the benefits of creating and dominating a niche market. From there, innovators can gradually expand into related and slightly broader markets, but that focus on technology and applications that make sense to a specific user base resonated in a big way with Resnick. In an industry where so many drone companies want to be everything to everyone, the company’s dedication to public safety has been a real differentiator for BRINC.

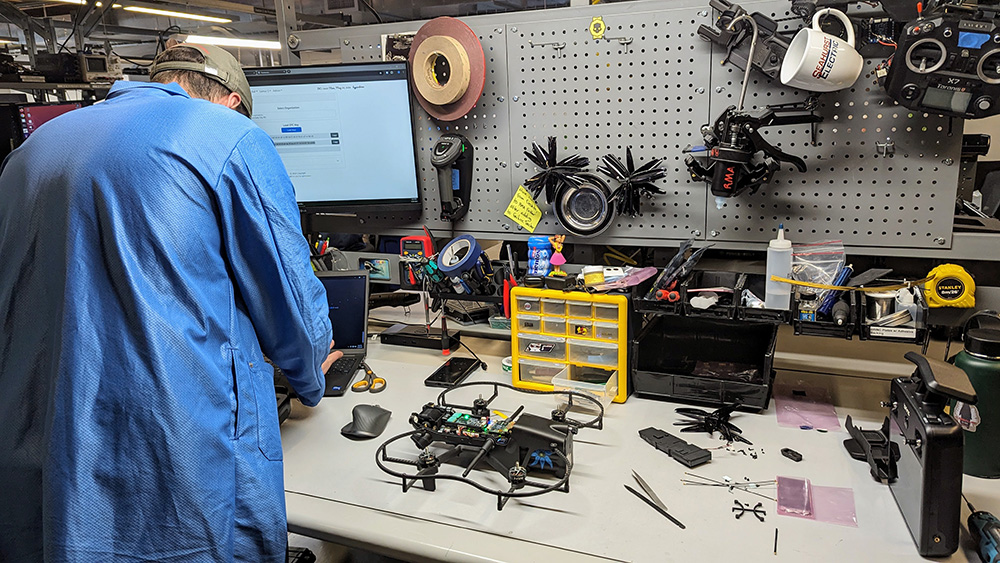

That focus is reflected in products like the Lemur 2, which was specifically designed to support SWAT operations. Featuring a two-way audio system, capabilities of operating in GPS-denied environments, as well as proprietary glass breaker technology, this focus helped them change perceptions about how the technology could be utilized in situations that require SWAT support.

This visit to the BRINC facility was complete with a glass breaker demo, and after witnessing it firsthand, I can say that the videos don’t do it justice. It’s a good illustration of the power and capability that can be developed for a set of niche end users in ways people on both sides of the solution can convey.

“It's the difference between a piece of technology being successful in the mission and it simply not doing what the users need,” Resnick explained. “A couple years ago, many of our customers were trying to use drones with prop guards inside, and it just didn't work. The drones would crash during the night or they’d lose a GPS signal and become uncontrollable. The right purpose-built solutions can open up whole new use cases for users that didn't exist before.”

The new Responder drone and Responder Station charging nest from BRINC are examples of this exact type of solution, with capabilities that allow the drones to arrive at 911 calls in less than 70 seconds as well as deliver life-saving medical payloads. These products are new parts of a connected ecosystem of tools from BRINC that are designed to enhance operational efficiency and also save lives.

Such a purposeful design provides users with options but also makes integration easier on every level. Many departments have resources that support the integration of new technology solutions, but regardless of their size or scope, having something that has been specifically designed for them put users in a much better position to move forward. Instead of a one-time use that depends on a specific pilot, this approach fosters a department-wide drone ecosystem. This approach equips the entire department with what they need to integrate the technology into established daily operations.

"The benefits really are innumerable, because having this kind of an ecosystem means you don't have to train people on numerous pieces of software and a bunch of distinct handheld controllers,” Resnick told Commercial UAV News. “It means you don’t need agreements with half a dozen different vendors to put together DFR programs; you only need one agreement that then allows everyone to get better using it in the same way. All of our technology operates in a similar way, so the people that have already adopted the Lemur 2 will find Responder incredibly easy to utilize.”

That’s a difference that departments like the Redmond Police are already supporting, which will only become more powerful with features like LiveOps and AR street overlays. BRINC LiveOps integrates live streaming, two-way communications, fleet, and evidence management into a single place, allowing users to instantly see all of their stations and locations in order to deploy drones autonomously. LiveOps can be the glue that holds these operations and integration together for an entire department in a way that is also scalable.

All of this highlights why so many people are specifically excited about the Responder drone and Responder Station charging nest. But as we walked around the facility, it was evident that such milestones aren’t as meaningful as the journey that has enabled them to be created. What makes these products and this company more than just another one that is trying to separate itself from the rest of the drone market?

American-made drones

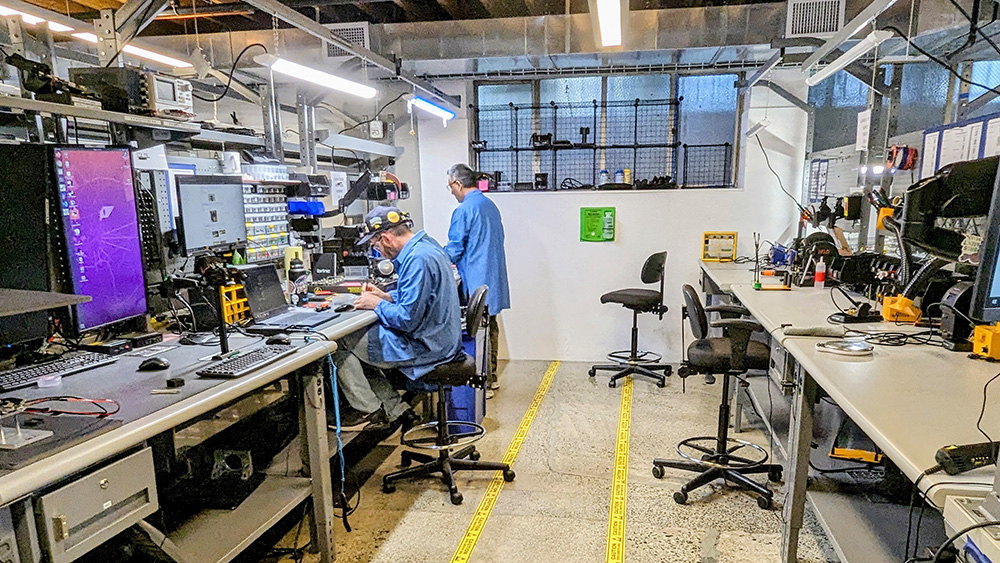

Walking through the BRINC production facility gives you a new appreciation for the supply chain challenges that others have not only struggled with but would also be the harbinger of the end of their business. The BRINC production facility features dedicated stations and people that support everything from manufacturing to assembly to testing, all of which is a reminder of how much it takes to not only defy the laws of gravity but also the laws of economics.

Putting his company in the best position to do both is why Resnick and BRINC are in Seattle to begin with. While Resnick might have started the company in his parent’s house in Las Vegas, a full production space was up and going just outside of the city very quickly. However, the challenges associated with finding a workforce that could best support BRINC defying gravity and dominating a market compelled him to look for a new location, resulting in the move to Seattle in 2021.

This approach has enabled BRINC to create NDAA-compliant drones, as well as position their solutions as being “made in America,” providing BRINC with a leg up when it comes to potential bans that have little to do with technology and everything to do with politics. While the US House Committee has advanced legislation to effectively ban DJI drones in the United States, none of that is connected to why BRINC is building out its engineering and manufacturing capabilities.

“There just aren't many hardware manufacturers in the United States and allied countries that can build these types of solutions,” Resnick said. “Even if we didn't want to do the hardware, we would essentially be forced to, because there's just no one else to work with. But scaling out our production capabilities like this has allowed us to build solutions that are more optimized for the use cases of our customers than anyone else. These are the only solutions in the market that can provide those sorts of capabilities, and I think that gives us an incredible competitive advantage.”

It’s an advantage that doesn’t come without an expensive commitment though, and it has subsumed entire drone companies over the past few years. It’s part of the reason that so many drone companies are trying to position their solutions as being applicable to multiple markets and users, as doing so theoretically allows them to capture revenue from multiple segments to help offset the incredible upfront and ongoing costs of production.

That exact approach is what Resnick sees as a further competitive advantage for his company though, because anyone taking that approach is offering a solution for multiple markets that doesn’t actually fit into any of them. It’s a difference you can see with the Lemur Glass Breaker attachment that is composed of tungsten carbide and spins up to 30,000 RPM. BRINC solutions like these only make sense for these users, but they also require a big engineering component. It’s something Resnick considered in great detail when putting together the Seattle office, compelling him to find inspiration from one of the most talented and prolific aircraft design engineers in the history of aviation.

“Kelly Johnson has talked about the importance of having manufacturing and assembly right next to one another, and we’ve seen that firsthand,” Resnick says, motioning to the upstairs and downstairs of the facility. “It allows both sides to be responsive and collaborate in a way that just doesn’t happen when you’re dealing with different locations.”

That sort of coordination and collaboration is foundational to the sort of purpose-built solutions that define user ecosystems, but these advantages aren’t specific to teams or departments. Instead, they’re connected to changes that are set to change expectations on every level.

Focusing on the real police and first response work

It’s no surprise to discover that police response times vary by city. But you’d be surprised just how long it can be. Across the United States, the average response time can be up to 15 minutes, with NPR recently reporting specifically why response times are taking longer. In 2022, NOLA.com reported that it took New Orleans police an average of 2½ hours to respond to a 911 call. Such response times are also a factor when it comes to delivering medical supplies to overdose victims.

This variance is on account of departments that have to quickly assess and address everything from cats stuck in trees to life-threatening emergencies, and everything in between. Police have needed to respond to each with the same level of initial urgency since they’re often acting with very little initial information, which means that knowing what they’re getting into could change the paradigm for the better. However, doing so would help with a challenge that goes beyond response times.

While it might be unnerving to learn about these response times, that response gap is what many criminals literally plan on. How would their considerations change if they knew some sort of response would be coming in a matter of seconds? Will the general public be able to change how they react in emergency situations thanks to two-way communication capabilities that can facilitate instruction and enhance de-escalation?

These are the sorts of questions that departments are working through in the present, but they’re not just about capabilities and benefits in the short term. They’re conversations that can enable changes in behavior and expectations in whole new ways.

“One thing I'm really excited about are joint police and fire DFR programs,” said Resnick. “We just saw a shared emergency response asset between police, fire and EMS in Fremont, California, and I think that's going to be a part of the future of this technology. Organizations can not only share the cost and the responsibility around running these programs but also share the benefits in a profound way. How can these resource be shared? Those are the sorts of questions that really allow you to build something.”

While the hostilities between police and fire personnel are well documented, sharing resources in this manner truly is something that makes sense for departments and the general public, highlighting why there’s been movement around such relationships. Security and logistical issues can be addressed with features like encryption keys and CJIS compliant platforms, while the installation of radio infrastructure by one department could extend the reach of a partner agency’s drone, all supported by BRINC. Their offering includes replacement drones, support with COA applications, ground-based radar, installation, transparency dashboards, and the accompanying teleoperations software suite.

This new approach to collaboration across industries is ultimately driven by the passion and interest that is foundational to drone technology and the industry itself, all of which connects to where BRINC is at today and where it’s headed in the near future.

Passion as a Driver for What’s Possible

For many years, an excessive amount of hype drove interest in the drone industry. With some specifically claiming that public safety applications were worth billions, the hype was out of control, causing many to focus on potential over reality. Thankfully, much of that subsided to give us an industry that is focused on what it means for drones to create value in the present, putting everyone in a better position than ever to grow. Of course, we could have said the same thing a year ago. Or two years ago. So what makes today different?

“What's different now is FAA reauthorization passing that mandates rulemaking on BVLOS operations,” Resnick said. “What’s changed is things like the Pearland Police Department getting a COA to operate their DFR program without human visual observers. What’s also new are products like the EchoShield from Echodyne that can detect manned aircraft and reroute drones around them. That combination of factors is going to result in widespread BVLOS approvals without a VO, which is really going to open up the market for DFR.”

Additionally, while the sheer speed of drone technology development has always been fast, Resnick mentioned how recent innovations truly represent something different. For many years, most drone hardware companies were playing catch up with DJI, with criticisms coming from users to say they simply wanted something comparable. Products like the Skydio X10 have been seen as game changers, which is an assertion Resnick agreed with. He mentioned there are now American drones on the market that can provide the same types of capabilities as the leading enterprise series DJI drones.

These changes are being driven by various individual companies and communities, but the path forward around collaboration and connection in public safety could prove to be especially instructive.

“People really are passionate about this technology,” Resnick said. “I know that’s true in various industries, but it’s especially true in the public safety space because it comes from a place of wanting to help in a space where there really aren’t competitive dynamics. A construction company might not necessarily want to share how they’re using drones to reduce inspection time with their competitors, but public safety agencies want to help keep their communities safe. It’s a positive feedback loop that’s driven by a passion that we see, feel and have for this space.”

That concept of passion underlays so much of where the technology is at today and where it’s going. It works the same for BRINC as well as for Resnick himself, as I can’t help but connect that passion on the part of end users to his own backstory, as well as why he wanted me to hear that siren. It’s the sort of thing that’s contagious in a good way, helping to change expectations and open up opportunities.

All of which is being driven by what’s perceptible with the technology rather than what’s possible...and that includes sirens that are as striking as they are revealing in terms of what we can expect from BRINC.

“The siren is annoyingly loud,” Resnick said with a laugh. “But that’s quite purposeful given the police needs and applications. It’s our goal to see that same type of purposefulness in every one of our products because we want agencies to be successful with our technology.”

Comments