Defining and enabling a UAS traffic management (UTM) system for drones is something we’ve talked about for years now, with many people believing that such an ecosystem will be the only way companies can operate a drone beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) at scale to truly enable commercial opportunities with the technology. This sort of UTM ecosystem will also completely change the paradigm around urban air mobility logistics.

Andy Thurling, Chief Technology Officer at NUAIR, has been intimately involved in the effort to enable this kind of ecosystem. He leads technical research on current and future UAS technologies and evaluates potential paths to implementation, and these endeavors were on full display at recent industry events. His session at the Commercial UAV Expo explored how different stakeholders have defined and are approaching the developments of a UTM system, while his XPONENTIAL panel detailed what it will mean to field UTM capability to support civil operations.

Those sessions are available to watch on-demand and they contain a plethora of technical details around how these UTM ecosystems are taking shape from a multitude of perspectives. However, I wanted to get a better baseline around the short and long-term impact we might see from such endeavors. To do so, I connected with Andy to ask him about the economic impact of drone technology that NUAIR has quantified, what makes L-BVLOS operations so important, whether there are distinct visions around how a UTM system is going to work and much more.

Jeremiah Karpowicz: NUAIR is focused on helping to generate an economic impact in the New York region that will come from civil drone operations being enabled. What are some of the ways you’re focused on measuring or seeing that impact?

Andy Thurling: We’ve been able to bring hundreds of jobs and millions of dollars into the area, but I think what's really important to note is that it's not just about the measurables. The technological ecosystem that we’ve helped create in Central New York to enable job growth and continue to draw in new companies to put down roots and grow here represents so much more. I hate to use an over-used term, but it really is an ecosystem.

NUAIR was founded by members of CenterState CEO in response to Central New York receiving a large Upstate Revitalization Initiative (URI) grant from New York State called “CNY Rising” – our region’s comprehensive strategy to revitalize communities and grow the economy. CNY Rising also led to the creation of the New York UAS Test Site at Griffiss International Airport, one of only seven FAA-designated UAS Test Sites in the United States. The GENIUS NY program is the world's largest business competition, and we’ve seen a lot of great start-up companies come out of that program. So we’ve got the startup culture with GENIUS NY, as well as the FAA-designated UAS Test Site out at Griffiss, which kind of acts as the glue to pull it all together. And then CenterState cultivates that economic activity. We really have this coalition of groups that are working together to advance the UAS industry and stimulate the economy.

Ultimately, how you count jobs and quantify the return on the investments that you’re asking about is kind of a black art, but all of these companies are operating to some extent in Central New York, and some of them quite a lot. They’re hiring people in Central New York and making the area the base of their operations. Top all this off with the additional revenue local restaurant and lodging establishments are getting from those companies who travel from all across the world to come test at the Test Site and end up staying for days or weeks at a time.

Calling that kind of measurement a “black art” is so true, because this kind of value isn’t just about the bottom dollar, is it?

It’s not, and you can really see that when you realize that we don’t actually charge for the support we provide to state agencies like the Department of Environmental Conservation or to the State Troopers. We do keep track of the time though, so when we get questions about the kind of economic impact that we’ve had, we can say we’ve spent X amount of hours with the State Troopers, and at a consultant rate of Y dollars per hour, so we’re able to take credit for the work that we do, even if there is no actual income that we see. We’re still making a positive impact for public agencies that is indirectly reflected in their bottom line.

It’s important for us to keep track of that so that the taxpayers can understand the value of what we do. It’s not just NUAIR, because this technology ends up as part of the ecosystem, and this all started with state investment and the support of the local community and the business community.

Being part of an ecosystem ties into your responsibility to the FAA and to NASA to conduct operations for UAS testing since you’re one of the seven FAA-designated UAS test sites in the United States. But that’s a much different kind of ecosystem, isn’t it?

It very much is, but if you’re talking about our responsibility in that ecosystem, it’s especially distinct because of how we have to approach being part of it.

The FAA and NASA don't provide us funding for continual operations because it’s all on a project-by-project basis. When NASA and the FAA have a project, they put out an RFI or an RFP, and we, along with all the other test sites, will answer it. Based on the strength of that application, the FAA, or NASA, decides whom they're going to fund to do that testing. We’ve been fortunate, as we’ve been selected for several of those, including UPP2, most of the TCLs and the NASA Vertiport. We’re here to serve the research and regulatory environment when they need us.

That need for the exact type of research you’re doing was at the heart of your Commercial UAV Expo panel, where you touched on some of the testing you’re doing as part of what you defined as local BVLOS (L-BVLOS) operations, which is a drone operation that occurs within the confines of an explicitly defined, relatively constrained environment. Briefly, what can you say about the problems that L-BVLOS solves?

There are so many moving parts to a UTM ecosystem that will support safe BVLOS operations. Consider that if I'm flying from point A to point B over 20 kilometers, I need to know over those 20 kilometers where all the obstructions are, what all of my comms coverages might look like and what the micro-climate is going to be for that whole route. I need some kind of means to verify that I don't have an air threat. What about the roads I'm flying over? I need to know where the people are and I need to know where the cars are. These are all very serious concerns for the FAA in truly long-distance, BVLOS operations.

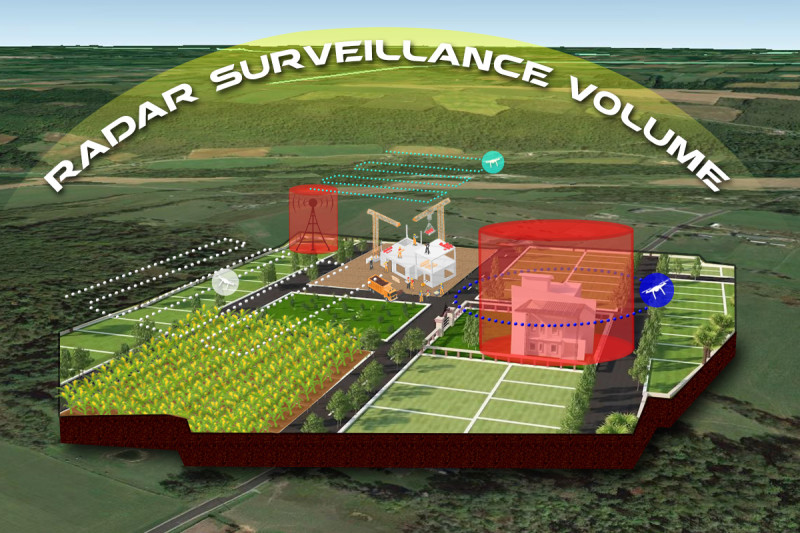

L-BVLOS

With L-BVLOS, we’re dealing with a constrained, well-defined area where I can more easily measure all those things I need to know. It’s a much more tractable way to solve this problem. This can support a “drone in a box” type of operation that gives you a very viable economic case, the type of which we could close rapidly in New York. And we already have everything we need to enable it.

Having everything you need right now makes this a matter of testing and proving your safety case when it comes to these types of operations, but during your sessions, you talked about how that process often puts you in an endless loop of “it depends” when it comes to defining safety standards for these types of operations. What’s the best approach to getting out of that loop?

It all comes down to the performance requirements that say how well we need to operate. And that's the key because we need to define the performance needs of each of these components in order to create this safe operation. We end up doing demo after demo but that doesn’t do much more than prove you can do something safely on that particular day.

I talked about the standards for the detect and avoid (DAA) performance during the Commercial UAV Expo panel and that tells you how well you need to do the mitigation. It tells you that you need to mitigate 60% or 70% or 82% of the conflicts. Those need to become non-conflicts with your mitigation in place. Because that's what's expected in the performance standard. They don't tell you how to do that though, so it’s kind of up to the test method standard. It lines up with how the FAA has rewritten Part 23 to be more performance-based. They tell you what they want to achieve, but they don't tell you necessarily how to do it.

ACAS Detect and Avoid

But that’s a good thing, isn’t it? That makes it technology agnostic, doesn’t it?

Yes, but when you go to the FAA and tell them you meet the performance-based requirement, they’re going to ask “how”. So that will be an inherent part of the discussion anyway, but it’s not a rule like it was under the old Part 23, which was more prescriptive. The new rule says you just have to meet this performance-based requirement, but you can come up with your own methods of compliance, which is the beauty of the performance-based rules. They are inherently more resilient to change.

That kind of give-and-take with the FAA factors into a comment from your AUVSI panel, where Jarret Larrow from the FAA talked about their vision for UTM, which included a new regulatory framework and an all-encompassing data exchange. What’s the biggest hurdle to establishing this framework? Is it related to costs, or preemption, or something else?

To a large extent, the vision that the FAA has laid out is one all of the people on that panel agree with, but there are different flavors of people's opinions about how to go about it. With UTM, you have some companies who have a very centralized perspective and believe that we’ll only have one USS. This is more prevalent in the European countries, where the U-Space concept essentially defines one main USS that will be primarily responsible for performing most of the safety-critical services. Of course, there will be various services from other USS providers, and they still need a pseudo-federated environment, which is what the UTM that NASA defined started with.

From NASA’s perspective, it’s always been fully-federated, where the FAA is the gateway. So they set constraints and receive information if it’s going to impact other air traffic. Beyond that though, everything is up to the USS’ to manage between themselves without anyone really being in charge. That’s been a challenge, because when you get into those interrelated and cloud-based scenarios, security becomes a big issue. That becomes further complicated because what it means to talk about security with the operators is different from how a cyber security expert might talk about these details, but we've got to talk in the language that the operator is going to understand.

I’m sensitive to this because the cyber security community has been through quite a lot around these terminology specifics. Ultimately, we’re not trying to change their terminology, but instead talk about it in terminology that can be understood by an operator, not by a cyber security expert. So that's been a challenge, but we're getting past that.

Some of that relates to a comment you made earlier about having everything we need right now to enable L-BVLOS, which sometimes makes it feel like the challenges with enabling this technology aren’t about the technology itself. They’re more about people or processes. But there are always new and different technology challenges to sort through as these systems form and evolve, aren’t there?

My background is military flight-testing, so I’ve seen first-hand how challenging it gets when systems become more interconnected and more software dependent. Fixing something becomes that much more complicated. You need a lot of discipline around processes and procedures to do regression testing, and it costs money, and it takes time.

Everyone in the UTM ecosystem wants to be that much more agile, but when they release a new product or push out an update, they need to know they didn't break something. When we fix something, we need to know we’re still in compliance with overall performance requirements. And that’s another reason why we started with Local-BVLOS, because the broader system performance requirements themselves were undefined. But, with L-BVLOS, I don’t need to know where every obstacle in Oneida County is located; I just need to know the height and location of the tower that’s near the area I want to fly and how it could affect my operation. And if we need to get that specific with other variables, I can measure them precisely as well.

These are technical challenges, and it’s why one of the whitepapers I have floating around is focused on putting a finer point on how we talk about different types of altitude datums and understanding how that affects interoperability. Interoperability, in this case, means when your UTM world touches the real world and there are things like trees and towers and other airplanes that you don’t want to run into. You need to understand that GPS altitude is measured from an imaginary line and not the “real world”, and those challenges are technical, processes, and people!

What are some of the developments you’re most looking forward to seeing come together for UTM ecosystems in the short term and long term?

I'm certainly looking forward to the results you’ll be seeing from the New York UAS Test Site. It’s hard to make a safety case without having some means of saying that an operation meets a certain level of performance. We’re working on a standard for the performance that a surveillance system needs to meet as well as a standard that will define how these systems communicate. It’s basically a full-stack, technology agnostic standard that defines how we can communicate within and vet our surveillance systems.

Beyond that, I want to see what kind of legal instruments are going to be defined between operators and service providers so that the risk is mitigated, and liability apportioned. How do we use UTM to mitigate the risks? There are so many moving pieces and that’s also why L-BVLOS makes a lot of sense. With L-BVLOS, I don't even need a service level agreement with a ground risk provider for most types of operation. If I'm doing precision agriculture, and there's a plot of land, I don't need a fancy service provider because I can handle that myself. It creates a path forward because it’s engineering 101. Simplify the problem, solve this problem. And once you get the solution to that problem, it can lead to other solutions. That’s what you get with L-BVLOS and I’m excited to see what it further defines.

Comments