For years now we have been hearing about the promise of a different kind of air transportation, Urban Air Mobility (UAM) or Advanced Air Mobility (AAM), as NASA likes to call it. Most, if not all designs, we have seen so far are purely electric in what has become a well-known acronym eVTOL (electric vertical takeoff and landing). Unfortunately, the crude reality is that a battery-only approach severely limits the endurance and payload of any aerial vehicle. This is very different when we deal with terrestrial vehicles or electric cars, which can function for hundreds of miles without recharging or overheating.

The battery industry has almost exhausted the growth potential of existing chemistry. The need for new compounds and innovation grows, as reality of these limitations sets in. Unfortunately for the aircraft industry, the real market for batteries lies in the car industry rather than the aerospace industry, and therefore the appetite for large investments in R&D is largely absent.

Let us be realistic, the non-traditional aviation industry must look elsewhere for the answers to increase flying time and heavier payloads. One quick alternative is the use of hybrid models, as in the case of sUAV (small unmanned aerial vehicles) where innovators such as Parallel Flight Technologies, Skyfront, and many others have obtained great efficiencies from small internal combustion engines to generate the energy used to power their electric motors.

Now, a new company, PARAGON VTOL Aerospace has launched an initiative to create the first hybrid UAM vehicle by adding an internal combustion engine to the energy mix to increase flying time and useful payload.

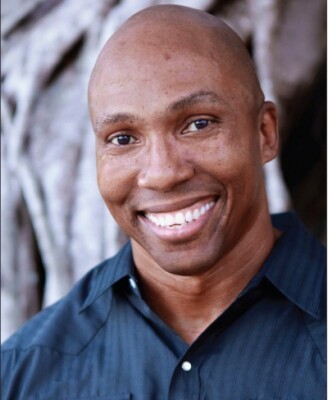

The Brownsville, Texas based company is working with a multidisciplinary group of consultants worldwide to finalize the design of its hybrid VTOL aircraft. We reached out to Dwight T. Smith, PARAGON VTOL’s founder and Chief Visionary Officer, for an exclusive interview on the details of his design and the merits of using a hybrid model.

The Brownsville, Texas based company is working with a multidisciplinary group of consultants worldwide to finalize the design of its hybrid VTOL aircraft. We reached out to Dwight T. Smith, PARAGON VTOL’s founder and Chief Visionary Officer, for an exclusive interview on the details of his design and the merits of using a hybrid model.

“Very early on, we came to the conclusion that a purely electric system was not the answer,” Dwight explained. “Obstacles to our original goals of endurance and useful payload were evident from day one, so we opted for a hybrid configuration and soon found out that off-the-shelf parts available in the marketplace were also a big obstacle to our vision.”

When addressing the lack of an adequate energy source to power non-traditional aircraft, Dwight was emphatic about the shortcomings of current battery technology.

“The battery industry has failed us in five specific areas,” Dwight stated emphatically. “Density, Thermal, payload, lifecycle and supply chain. Unless we address all five elements, battery-only solutions are a non-starter. We have seen with surprise how our competitors claim to have long flights and heavy payloads using only batteries and our research tells us that this not feasible, so somebody is looking at the wrong data here.”

The issue of purely electrical designs naturally evolved into a discussion of what kind of ground infrastructure would be necessary to support 24/7 operations in congested urban areas.

“The key to success in this new transportation arena lies in our ability to develop and implement ground infrastructure capable of maintaining constant arrivals and departures with the same efficiency or better than current airport operations,” Dwight said. “Overheated batteries and special contraptions to handle hot elements are not the answer, we need to be as effective, safe and brief as airports today, but in a simpler environment such as rooftops of existing buildings. It will be very difficult to build new infrastructure and we will, as an industry, have to face the reality that adapting what’s already out there is the way to go.”

When the conversation turned to time-to-market and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certification, Dwight will be careful with his approach, ensuring it is ready to meet the demands of the FAA.

“We are planning to have over one million hours of flying data before we attempt FAA certification,” he said bluntly. “We are determined to find the flaws in our design and fix them before we approach the regulator for certification. We want to build a safe, reliable and realistic aircraft that would be able to open the doors to a new and inexpensive way to transport people.”

It certainly sounds ambitious, but we are encouraged by PARAGON’s candid approach to solving the issue of flying time and heavy payload ratios that has and will continue to challenge this industry for years to come.

Comments