We often focus on the ways in which small drones are making a difference in terms of making a given task faster, cheaper or safer, and those differences have made a real impact in industries that range from energy to construction to agriculture. At the other end of the spectrum, there’s lots of excitement about drone taxis that will someday function in urban air mobility (UAM) ecosystems that will completely redefine expectations around how we travel. But what does the middle ground between these two solutions look like?

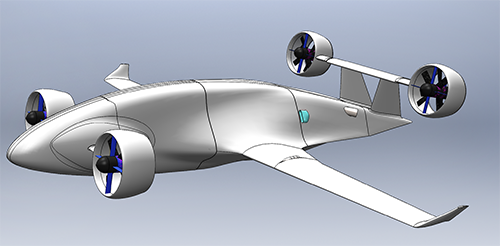

Heavy-lift cargo carrier drones have been making headlines of late, and while the technology doesn’t fit perfectly between the small drones of today and the drone taxis of tomorrow, their ability to carry air cargo in various conditions to remote locations represents a powerful use case. This type of aircraft could be a game-changer for the air cargo industry, although it could make a real difference in a variety of sectors.To learn more about what those differences could look like, we got in touch with Ed De Reyes, CEO and co-founder of Sabrewing Aircraft, Inc. His company is a manufacturer of unmanned heavy-lift commercial cargo air vehicles whose technologies and products are designed to transform the way the world ships air-cargo. We talked with him about whether or not heavy-lift cargo drones can be a “bridge” to enabling UAM ecosystems, the specific advantages that heavy-lift cargo drones represent, what milestones with this technology we should be looking out for and much more. Jeremiah Karpowicz: We hear a lot about the delivery drones of today, and also the drone taxis of tomorrow, but I must admit, the technology that feels like it’s between those two solutions, heavy-lift cargo carrier drones, don’t always make headlines. Why do you think that is?Ed De Reyes: The toy drones (those under 55 pounds/22kg) have dominated the market - and are more readily available to the public. The “cargo” drones in the news have been dominated by the so-called “last mile” delivery drones that can deliver a burrito or a couple of band-aids – but these drones can’t fly more than a few miles or in bad weather. They also can’t carry more than a few items for very short distances…but the very fact that you can, at some time in the future, order something on your cell phone and have it delivered to your house is very appealing to the masses.News about larger drones that can deliver tons of cargo to remote locations doesn’t appeal to the mass market as much as a toy drone delivering tacos (except may to people living in remote areas). Are there specific advantages that cargo carrier drones represent when compared to smaller drones? There are so many advantages that it’s difficult to pick two or three - but I’ll try.First of all, instead of carrying burritos or bandaids or a bucket of fried chicken - we can carry entire medical suites and entire kitchens full of food. Secondarily, we can carry a cargo load of up to 6000 pounds (2700 kg) for 1000 miles (1800 km) in any weather. We can do this in environmental conditions where no toy drone can go – and do it reliably – to the most remote parts of the Earth. Where a toy drone can carry a bottle of water, a vial of medicine or liter of blood a few miles in a natural disaster, you’ll have to get close enough to that natural disaster to get that drone in and out. If you’re delivering by parachute, you’re still faced with the dilemma of delivering hundreds of bottles of water and gallons of blood and tons of medicine into a disaster area. You could literally fly toy drone flights around the clock for days and not reach a quarter of the load that our Rhaegal aircraft can carry in one single load.Admittedly, our drone isn’t economical to carry a slice of pizza to the house three blocks away…but there aren’t many remote villages that care much about ordering a slice of pizza to go hundreds of miles. As we say in the cargo drone business: “Give a nearby village a slice of pizza and they feed 1 person for one small meal. Give a remote village a cargo load of sausage, cheese, flour and tomato sauce - and they can feed their entire village for weeks.” Is it useful to think of heavy-lift cargo UAVs as a “bridge” to the eventual technology and regulatory environment that we’ll need to enable true urban air mobility? This is an excellent observation on your part - and one that others are beginning to realize as well. I’ve spent the last 31 years representing companies who are seeking FAA and other regulatory agency approvals for their aircraft. In that time, I’ve come to know a number of regulators who shared their private thoughts regarding Urban Air Mobility and manned eVTOL. Privately, everyone has shared the fact that there are no regulations in existence that allow a concept such as the Uber Elevate espouses to become a reality by 2025…much less by 2023. The process towards creating regulation is getting better than it was even 5 years ago, but the creation of regulation is still not a speedy process.These regulators have also stated that it would be far easier to build and certificate an unmanned cargo aircraft using today’s existing regulations than it would be to build something that resembles a (manned) helicopter for short-distance mass transit. This is based on the fact that there are specific regulations for the carriage of humans - such as seat rails, interior fire-resistant and non-toxic materials, instruments and other items required on-board the aircraft that must be included in order to obtain type certification. Unmanned cargo aircraft carry no people - or pilots - and therefore do not have to comply with those regulations that assure the safety of passengers or crew. Not that these aircraft aren’t safe; they are by regulation - but the requirements for passenger seat rails that can withstand 9 g’s of force in a crash and non-flammable headliners simply aren’t required.Privately, the sentiment amongst regulators - not only the FAA but EASA, Air Transport Canada and several other regulatory entities is that the “low-hanging fruit” for eVTOLs is the certification of unmanned cargo first; using the experience and lessons learned in unmanned cargo, it would be possible to certificate a manned version quickly and fairly easily once everyone (including the regulatory agency) knows how to proceed. What are some of the regulatory hurdles that are associated with cargo carrier drones?Surprisingly, there aren’t as many as you would think. The (U.S.) Department of Defense has been flying the RQ-4 Global Hawk for 20 years and the MQ-1 Predator for 25 years in the national airspace; this has led to a sense of how unmanned aircraft can and should be operated. The Global Hawk weighs in at just over 32,000 pounds (14,500 kg) - and flies regularly in the skies between Southern California, North Dakota, and locations in the Middle East in the national airspace. Operation of these aircraft isn’t anything new, so from the very start, several of our employees (me included) have extensive Global Hawk operations experience - so patterning our flight operation and use after the Global Hawk was a point of familiarity not only for Sabrewing Aircraft but for the FAA as well. This was key to many of our favorable conversations and program reviews with the FAA. We’ve worked from the very beginning to anticipate many of the questions that the FAA has had regarding how we intend to assure safety of lives on the ground - as well as how the aircraft will be operated in national airspace - making our plan less of a regulatory hurdle than even some manned aircraft designed to fly cargo.We’ve also partnered with a number of companies and universities that agree with us that our approach to unmanned flight is the right path - and who are also providing expertise, material and certificated parts to help easy our regulatory path – such as Rolls Royce, Toray, Garmin, Cobham SatCom, and FLIR - as well help from universities as Oklahoma University (OU) and California State University Channel Islands. Does the pilot requirement to operate cargo carrier drones represent an additional hurdle when it comes to adoption?Again, we were fortunate to have the Global Hawk program as an excellent reference base. Because of the amount of automation and a robust autopilot, the Air Force requirement for pilots operating the Global Hawk are a Commercial/Instrument “ticket”. This is different from traditional FAR Part 135 pilot requirements flying turbojet or turboprop aircraft that require an Air Transport Pilot (ATP) rating. Even though our aircraft will be operated by firms who hold a Part 135 certificate, they will be able to utilize pilots with a commercial certification with an instrument endorsement.The FAA has agreed with us that the level of automation on our aircraft is sufficient to be operated by a pilot with a commercial/instrument license. This fact alone has very significant implications for relieving the current pilot shortage, and could possibly be a faster path towards a full ATP license. What are some of the ways this technology is being utilized today? As previously mentioned, the military is operating large unmanned aircraft in the national airspace today…and doing so successfully. In the 25 years that there have been large semi-autonomous UAVs operating in the national airspace, not one life has been lost to mishaps. That is a record that has never been achieved by manned operations.Secondarily, fly-by-wire and traffic collision avoidance systems (“TCAS”) - is being used daily by even small, private, general aviation aircraft. These systems are the core of our aircraft being able to avoid other traffic in the air…or even being able to land in a spot that’s only the size of two semi-tractor-trailer rigs parked side-by-side…without needing any human intervention. All of these technologies have been successfully demonstrated and exist - on the market - today. We’ve heard about how companies like UPS and DHL are looking at utilizing drones to make deliveries in remote locations, but this technology takes that concept to a different scale, doesn’t it?This is a fact.One of the use cases that we had previously presented was the case of a cargo carrier company landing in late in very foggy weather at the San Bernardino (California) Logistics Airport. The crew “breaks down” the cargo load from the large cargo aircraft – in this case an MD-11F – and taking 6000 pound (2700 kg) loads and placing them in our aircraft. Our aircraft would be able to take off in zero/zero visibility and fly to a processing facility in Oxnard, California (about 100 miles away) in about 30 minutes. Our UAV lands in the parking lot of the processing facility, the large cargo load is removed and 1000 pound (454 kg) load is loaded back aboard, and the UAV lifts off and lands at a smaller processing center in Beverly Hills and that cargo is unloaded. Cargo bound for other locations is loaded back on to our UAV and flown back to Oxnard. Once there, it’s unloaded, reloaded and sent to Tehachapi - where the weather is heavy snow and gusts to 60 knots (111 kph) and heavy icing conditions. The ground where our UAV lands is slushy mud and snow, and impossible to get a forklift or pallet jack there to unload our cargo…so our aircraft can discharge the cargo container without any ground handlers needing to remove it.These are all real scenarios that the cargo companies see on a regular basis…and they only make money when that cargo gets to its destination, and our aircraft is that “guarantee” in their overnight delivery pledge…making it a very attractive prospect for any cargo company. Along those same lines, we’ve heard about drones being used to deliver medical supplies in an especially efficient way, but again, cargo carrier drones could scale that concept up in a powerful way, correct?There are currently several companies delivering medical supplies to remote locations - which is excellent, given that the need has existed for millennia but hasn’t really had a solution until now.The drawbacks with the technology in use are that these aircraft can’t really operate in high winds or even in known icing conditions – which limits their use during weather-related disasters. It also means that the limited cargo size of these current applications limits the amount of blood, medicine or other life-saving supplies can provide two or three people with needed care - but what if there are hundreds? How do you prioritize 50 or 60 critical patients that need blood or medicine? Distance works against these smaller-capacity aircraft as well: in order to carry blood to a distant location using a slow-flying drone, you would have to keep the blood cold via ice packs or a refrigeration device of some sort. These add weight to the cargo and decreases either distance or the size of the load.Our aircraft, by comparison, is extremely versatile. Replacing cargo with fuel, it can fly up to 7000 nautical miles to a location where it can be loaded with cargo (instead of fuel) and fly directly to a disaster area - with tons of food, fuel, water, medical supplies - even communications gear to give immediate relief. It can do this regardless of the weather. We have the ability to transport entire medical suites with all the gear and medicine required. We even have the capability of supplying up to 500 kW of electrical power - enough to power 250 homes with emergency power days. If our aircraft had been available during Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, things would certainly have turned out much differently than what we witnessed. What about companies like Amazon? How will they utilize this technology? Our aircraft can help alleviate road congestion - yet deliver goods to warehouses and stores much faster than with other means.For a company like Amazon (that operates in a similar way to a FedEx or UPS or DHL), our Rhaegal is perfect for the mission I described earlier: transporting goods taken from a large cargo aircraft such as an MD-11F, an Airbus A300 or a 747 Freighter and move up to 6000 pounds of cargo to waiting truck over 1000 miles away - for speedier delivery of goods. It also allows for a “pop-up” distribution center at an airport or even a parking lot, where our aircraft can land, cargo handlers can unload the cargo and then backhaul cargo to the main logistics base. How are warehouses and facilities able to utilize this technology? Are there any that are doing so right now? We’ve had requests for information from manufacturers throughout the world looking to be able to move pieces, parts and finished goods between locations and warehouses. One inquiry that is still ongoing is an auto manufacturer - to move parts between assembly plants and to make sure that an assembly line is down for only a few minutes…as opposed to hours or days. We’re also in discussions with a multi-national oil exploration company that is evaluating the ability to move large loads of well casing, drill bits, tools and even supplies between locations on the North Slope in Alaska.Since we’ve introduced our Rhaegal aircraft over 18 months ago, our customers have helped to define its mission and use cases…far surpassing how we envisioned it being used…but well within its capabilities. What future applications of the technology have you most excited? All are exciting - but the ones that hold the most promise is our aircraft use by the US Department of Defense for Forward Area Re-Supply – and possibly casualty evacuation. The ability to save lives grows significantly higher the faster you can get a casualty to a hospital, and our aircraft can fly as fast as 200 knots (370 kph). That’s much faster than a helicopter but more maneuverable (and makes less of a target) than a V-22 Osprey.Another is the disaster relief mission - where our aircraft can bring food, fuel, water, supplies, medicine, communications and even electrical power to areas that are hard-hit by natural or man-made disasters - and can do so faster and more efficiently than any other platform.Surprisingly, in places like Alaska, only 17% of the communities where there is a year-round population have access to roads, airports, railroads or even water ports. Even those with airports are limited in the winter, and even those with airports and water ports are limited by weather and winds. Our aircraft was designed from the start to get the cargo there - regardless of the environment. Are there any milestones that we should be keeping an eye out for when it comes to technology or regulatory advances with cargo carrier drones?There are a number of companies springing up now in the unmanned cargo space. It’s an old, overused adage, but I believe in, “If you build it, they will come”. We’ve already seen that with our aircraft: our customers are defining and re-defining use cases and methods of employment. So much so that we’ve re-written our Concept of Operations document a couple of times based on ideas provided to us by our customers.I’d say that if you keep an eye on who is buying our aircraft - or Elroy Air’s customers or Natilus’ customers, you’ll see the dominos begin to fall and other companies will do so very quickly. Our sales order book has grown exponentially in the last 6 months, and we expect that our customers, and those of Elroy and Natilus and Dronamics and some of the newer companies in the large cargo aircraft business will lead to faster implementation of aircraft certification.

Is it useful to think of heavy-lift cargo UAVs as a “bridge” to the eventual technology and regulatory environment that we’ll need to enable true urban air mobility? This is an excellent observation on your part - and one that others are beginning to realize as well. I’ve spent the last 31 years representing companies who are seeking FAA and other regulatory agency approvals for their aircraft. In that time, I’ve come to know a number of regulators who shared their private thoughts regarding Urban Air Mobility and manned eVTOL. Privately, everyone has shared the fact that there are no regulations in existence that allow a concept such as the Uber Elevate espouses to become a reality by 2025…much less by 2023. The process towards creating regulation is getting better than it was even 5 years ago, but the creation of regulation is still not a speedy process.These regulators have also stated that it would be far easier to build and certificate an unmanned cargo aircraft using today’s existing regulations than it would be to build something that resembles a (manned) helicopter for short-distance mass transit. This is based on the fact that there are specific regulations for the carriage of humans - such as seat rails, interior fire-resistant and non-toxic materials, instruments and other items required on-board the aircraft that must be included in order to obtain type certification. Unmanned cargo aircraft carry no people - or pilots - and therefore do not have to comply with those regulations that assure the safety of passengers or crew. Not that these aircraft aren’t safe; they are by regulation - but the requirements for passenger seat rails that can withstand 9 g’s of force in a crash and non-flammable headliners simply aren’t required.Privately, the sentiment amongst regulators - not only the FAA but EASA, Air Transport Canada and several other regulatory entities is that the “low-hanging fruit” for eVTOLs is the certification of unmanned cargo first; using the experience and lessons learned in unmanned cargo, it would be possible to certificate a manned version quickly and fairly easily once everyone (including the regulatory agency) knows how to proceed. What are some of the regulatory hurdles that are associated with cargo carrier drones?Surprisingly, there aren’t as many as you would think. The (U.S.) Department of Defense has been flying the RQ-4 Global Hawk for 20 years and the MQ-1 Predator for 25 years in the national airspace; this has led to a sense of how unmanned aircraft can and should be operated. The Global Hawk weighs in at just over 32,000 pounds (14,500 kg) - and flies regularly in the skies between Southern California, North Dakota, and locations in the Middle East in the national airspace. Operation of these aircraft isn’t anything new, so from the very start, several of our employees (me included) have extensive Global Hawk operations experience - so patterning our flight operation and use after the Global Hawk was a point of familiarity not only for Sabrewing Aircraft but for the FAA as well. This was key to many of our favorable conversations and program reviews with the FAA. We’ve worked from the very beginning to anticipate many of the questions that the FAA has had regarding how we intend to assure safety of lives on the ground - as well as how the aircraft will be operated in national airspace - making our plan less of a regulatory hurdle than even some manned aircraft designed to fly cargo.We’ve also partnered with a number of companies and universities that agree with us that our approach to unmanned flight is the right path - and who are also providing expertise, material and certificated parts to help easy our regulatory path – such as Rolls Royce, Toray, Garmin, Cobham SatCom, and FLIR - as well help from universities as Oklahoma University (OU) and California State University Channel Islands. Does the pilot requirement to operate cargo carrier drones represent an additional hurdle when it comes to adoption?Again, we were fortunate to have the Global Hawk program as an excellent reference base. Because of the amount of automation and a robust autopilot, the Air Force requirement for pilots operating the Global Hawk are a Commercial/Instrument “ticket”. This is different from traditional FAR Part 135 pilot requirements flying turbojet or turboprop aircraft that require an Air Transport Pilot (ATP) rating. Even though our aircraft will be operated by firms who hold a Part 135 certificate, they will be able to utilize pilots with a commercial certification with an instrument endorsement.The FAA has agreed with us that the level of automation on our aircraft is sufficient to be operated by a pilot with a commercial/instrument license. This fact alone has very significant implications for relieving the current pilot shortage, and could possibly be a faster path towards a full ATP license. What are some of the ways this technology is being utilized today? As previously mentioned, the military is operating large unmanned aircraft in the national airspace today…and doing so successfully. In the 25 years that there have been large semi-autonomous UAVs operating in the national airspace, not one life has been lost to mishaps. That is a record that has never been achieved by manned operations.Secondarily, fly-by-wire and traffic collision avoidance systems (“TCAS”) - is being used daily by even small, private, general aviation aircraft. These systems are the core of our aircraft being able to avoid other traffic in the air…or even being able to land in a spot that’s only the size of two semi-tractor-trailer rigs parked side-by-side…without needing any human intervention. All of these technologies have been successfully demonstrated and exist - on the market - today. We’ve heard about how companies like UPS and DHL are looking at utilizing drones to make deliveries in remote locations, but this technology takes that concept to a different scale, doesn’t it?This is a fact.One of the use cases that we had previously presented was the case of a cargo carrier company landing in late in very foggy weather at the San Bernardino (California) Logistics Airport. The crew “breaks down” the cargo load from the large cargo aircraft – in this case an MD-11F – and taking 6000 pound (2700 kg) loads and placing them in our aircraft. Our aircraft would be able to take off in zero/zero visibility and fly to a processing facility in Oxnard, California (about 100 miles away) in about 30 minutes. Our UAV lands in the parking lot of the processing facility, the large cargo load is removed and 1000 pound (454 kg) load is loaded back aboard, and the UAV lifts off and lands at a smaller processing center in Beverly Hills and that cargo is unloaded. Cargo bound for other locations is loaded back on to our UAV and flown back to Oxnard. Once there, it’s unloaded, reloaded and sent to Tehachapi - where the weather is heavy snow and gusts to 60 knots (111 kph) and heavy icing conditions. The ground where our UAV lands is slushy mud and snow, and impossible to get a forklift or pallet jack there to unload our cargo…so our aircraft can discharge the cargo container without any ground handlers needing to remove it.These are all real scenarios that the cargo companies see on a regular basis…and they only make money when that cargo gets to its destination, and our aircraft is that “guarantee” in their overnight delivery pledge…making it a very attractive prospect for any cargo company. Along those same lines, we’ve heard about drones being used to deliver medical supplies in an especially efficient way, but again, cargo carrier drones could scale that concept up in a powerful way, correct?There are currently several companies delivering medical supplies to remote locations - which is excellent, given that the need has existed for millennia but hasn’t really had a solution until now.The drawbacks with the technology in use are that these aircraft can’t really operate in high winds or even in known icing conditions – which limits their use during weather-related disasters. It also means that the limited cargo size of these current applications limits the amount of blood, medicine or other life-saving supplies can provide two or three people with needed care - but what if there are hundreds? How do you prioritize 50 or 60 critical patients that need blood or medicine? Distance works against these smaller-capacity aircraft as well: in order to carry blood to a distant location using a slow-flying drone, you would have to keep the blood cold via ice packs or a refrigeration device of some sort. These add weight to the cargo and decreases either distance or the size of the load.Our aircraft, by comparison, is extremely versatile. Replacing cargo with fuel, it can fly up to 7000 nautical miles to a location where it can be loaded with cargo (instead of fuel) and fly directly to a disaster area - with tons of food, fuel, water, medical supplies - even communications gear to give immediate relief. It can do this regardless of the weather. We have the ability to transport entire medical suites with all the gear and medicine required. We even have the capability of supplying up to 500 kW of electrical power - enough to power 250 homes with emergency power days. If our aircraft had been available during Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, things would certainly have turned out much differently than what we witnessed. What about companies like Amazon? How will they utilize this technology? Our aircraft can help alleviate road congestion - yet deliver goods to warehouses and stores much faster than with other means.For a company like Amazon (that operates in a similar way to a FedEx or UPS or DHL), our Rhaegal is perfect for the mission I described earlier: transporting goods taken from a large cargo aircraft such as an MD-11F, an Airbus A300 or a 747 Freighter and move up to 6000 pounds of cargo to waiting truck over 1000 miles away - for speedier delivery of goods. It also allows for a “pop-up” distribution center at an airport or even a parking lot, where our aircraft can land, cargo handlers can unload the cargo and then backhaul cargo to the main logistics base. How are warehouses and facilities able to utilize this technology? Are there any that are doing so right now? We’ve had requests for information from manufacturers throughout the world looking to be able to move pieces, parts and finished goods between locations and warehouses. One inquiry that is still ongoing is an auto manufacturer - to move parts between assembly plants and to make sure that an assembly line is down for only a few minutes…as opposed to hours or days. We’re also in discussions with a multi-national oil exploration company that is evaluating the ability to move large loads of well casing, drill bits, tools and even supplies between locations on the North Slope in Alaska.Since we’ve introduced our Rhaegal aircraft over 18 months ago, our customers have helped to define its mission and use cases…far surpassing how we envisioned it being used…but well within its capabilities. What future applications of the technology have you most excited? All are exciting - but the ones that hold the most promise is our aircraft use by the US Department of Defense for Forward Area Re-Supply – and possibly casualty evacuation. The ability to save lives grows significantly higher the faster you can get a casualty to a hospital, and our aircraft can fly as fast as 200 knots (370 kph). That’s much faster than a helicopter but more maneuverable (and makes less of a target) than a V-22 Osprey.Another is the disaster relief mission - where our aircraft can bring food, fuel, water, supplies, medicine, communications and even electrical power to areas that are hard-hit by natural or man-made disasters - and can do so faster and more efficiently than any other platform.Surprisingly, in places like Alaska, only 17% of the communities where there is a year-round population have access to roads, airports, railroads or even water ports. Even those with airports are limited in the winter, and even those with airports and water ports are limited by weather and winds. Our aircraft was designed from the start to get the cargo there - regardless of the environment. Are there any milestones that we should be keeping an eye out for when it comes to technology or regulatory advances with cargo carrier drones?There are a number of companies springing up now in the unmanned cargo space. It’s an old, overused adage, but I believe in, “If you build it, they will come”. We’ve already seen that with our aircraft: our customers are defining and re-defining use cases and methods of employment. So much so that we’ve re-written our Concept of Operations document a couple of times based on ideas provided to us by our customers.I’d say that if you keep an eye on who is buying our aircraft - or Elroy Air’s customers or Natilus’ customers, you’ll see the dominos begin to fall and other companies will do so very quickly. Our sales order book has grown exponentially in the last 6 months, and we expect that our customers, and those of Elroy and Natilus and Dronamics and some of the newer companies in the large cargo aircraft business will lead to faster implementation of aircraft certification.

Comments