Establishing a Drone Business with Part 107A five-part series exploring what it means to make drone technology make sense under Part 107Part 107 in Oil and Gas • Part 107 in Energy • Part 107 in Construction |

The potential impact drones may be able to make in a variety of commercial endeavors has been discussed for many years now, but Part 107 has allowed organizations to turn those conversations into bottom line results. The FAA's Small UAS Rule (aka Part 107) has made a major impact on how drones can and are being used across industries, including agriculture. The drone service sector is following suit, with more companies providing training for newcomers.

Such training can cost as little as a few hundred dollars, but it’s just the beginning. Investment in equipment and a myriad of other factors make starting a drone business serving any niche market a complicated process, but thanks to Part 107, more and more people are doing so and finding success. That includes seasoned drone consultants, as well as internal stakeholders at organizations seeking to develop their own drone program.

Clearer Skies

The incentives to hone in on UAS consulting for agriculture are obvious: even part-time drone consultants can make $20,000 to $30,000 per year serving an industry that is always plagued by weather-related variables. Some of the most successful drone consultants make six figures or more.

FAA guidelines have enabled more people to enter the drone industry, which is good for competition. But after receiving their license under Part 107, the drone operator must identify applications that will improve clients’ yields.

The best specialists know there’s no one-size-fits-all solution for gathering information via drones in agriculture. These consultants differentiate between the various crops being grown and their associated needs, tailoring their solution to best suit those needs. But drone industry experts advise that drone and data analysis experts should develop greater specializations in agriculture and a better understanding of the various types of farming—apple orchards not having the same needs as cornfields.

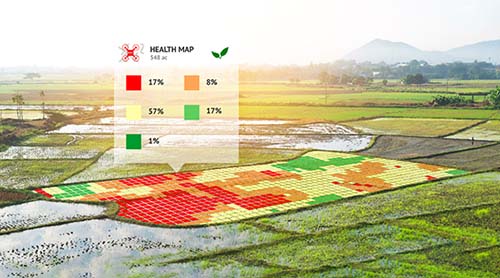

Software firms are catching on. Data analytics for agriculture are becoming more specialized, meeting the specific needs of the agriculture industry. And the features that farmers are seeking from drones depend upon their individual needs, though some common areas are covered. Soil analysis, planting, crop monitoring, crop spraying, crop health and irrigation are some of the most sought-after areas for drone-led inspections and data analysis.

Farmers today are using drones to capture imagery that automates plant counting, measures plant height, evaluates plant health, monitors field performance, identifies missed plantings and more. Drone tech also is helping the agriculture industry by generating plant counts and improving the accuracy of yield forecasts. Drones can help identify standing water, determine the extent of flood damage and monitor water features. They also monitor stockpiles of feed, fertilizer and other agriculture supplies.

For both farmers and some drone consultants, it’s challenging to change the way they approach a task, though change they must. Specialization is the rule in this niche.

“Today, the challenge isn’t flying the drone. Rather, it’s integrating the technology into the day-to-day operations of their farm.” says Thomas Haun, Executive Vice President at PrecisionHawk. “That can mean figuring out how a drone can be used specifically for crop scouting or using it to understand how someone should variable-rate their nitrogen. There are areas where there are very clear value propositions, but that depends on how someone wants to use the technology.”

The field is wide open. Drone service providers can position where and how they create value, by capturing the details.

“The more specific someone gets, the more we've seen them have success. If you're a crop consultant and the value you're providing is in variable rate prescriptions, that's probably the area you should start to introduce the technology,” Haun says. “That consultant can tell their client they're already giving them a variable rate nitrogen file for their applicator, but now they can use drone technology to enhance the robustness or granularity of that prescription. So, we've seen service providers have success when they already have a value proposition, and they're now enhancing this with that grower or farmer.”

Increasingly, crop consultants are specializing in certain crops, or in certain times in the growing season. Some go with the local flow.

“If you think about crop consultants, what they tend to do is look at their local geography, they understand where the value lies from a best practices perspective in terms of managing a crop and the crops that are growing in that region. They then focus there,” Haun says.

Practical Considerations

Practical Considerations

Drone aficionados who want to go pro, pros who want to do better under the new rules, or even newbies who want to learn to fly drones for agriculture, should consider several factors including hardware, insurance and waivers.

Hardware & Other Equipment

- Applications and services that the pilot wants to pursue will determine what type equipment they will need

- Hardware options include multi-rotor and fixed-wing models, as well as a variety of sensors and accessories

- Imaging and analytics capabilities are essential for agriculture. A software platform offering image stitching and analysis capabilities, along with support for outputs from thermal and other advanced sensors, are necessities

Safety & Insurance

- Drone service providers should carry hull and liability insurance, both for the equipment and bodily injury

- Service providers should develop a safety manual to ensure an OSHA-compliant and safe workplace environment

Waivers & Certifications

Part 107 provides a license for commercial drone operations, but some missions aren’t permitted. In agriculture, a waiver allowing operations beyond the visual line of sight (BVLOS) of the operator allows pilots to capture more area in a single deployment, compared to flying a drone within line of sight. While the process of securing a waiver may seem complex, there are resources available to help navigate the process.

Capturing Value

Capturing Value

Operators looking to launch a drone services business in agriculture need to:

- Understand the motivations and challenges of their prospective clients by learning about growing cycles, plant health, and crop threats

- Interpret data for their clients

- Price simply, by offering services at a flat rate, by the acre, or some combination of both

But what about BVLOS operations under Part 107? Should a user be more focused on creating value with what they can do under Part 107, or should they start the waiver process if that’s where they believe the true value lies?

“Currently, regulations limit drone operations to within visual line of site. If a service provider can deliver value to clients while operating within these limits, they should start there.” Haun says. “In BVLOS operations, there are several stages. In the first stage, an operator can extend visual line of site flight by adding visual observers throughout the area of interest. PrecisionHawk operates in the second stage, in which extended visual line of site missions may be executed over a 3-4 mile radius without additional visual observers—effectively, BVLOS flight. In the largest stage, operators can fly dozens—or soon hundreds—of miles away from the operator.”

“So, it really depends on someone's environment. But there are ways to get waivers today that are straightforward,” Haun said. “If that's going to change that value proposition, or change the cost equation of the service provision, then they should look into it.”

Many operators have been able to effectively sort through the waiver process, but the real value of the technology resides with an understanding around the drone itself as well as the data it’s capturing. That’s an understanding that can be achieved with Part 107 Certification, but anyone that has attained their certificate should realize that doing so is just the beginning of their journey, not the end of it.

“Drones are not a silver bullet,” Haun concluded. “They're not going to take your crop consulting business and turn it on its head. But they can augment that business and make it a lot better and a lot more effective. But you have to understand where the value lies in that information and in that data.”

Comments