At INTERGEO 2019, Jan Helge Mey took the stage to explain in great detail how the new regulations that are set to take effect across Europe in 2020 might impact commercial drone operations of all types. His perspective is an especially powerful one, as Jan is a partner with BHO Legal, which is a boutique law firm based in Cologne, Germany, with a focus on aerospace and high-technology projects. The firm was established ten years ago with founders having a background from the German Aerospace Center and international law firms. It positioned itself right from the start as a boutique law firm that focuses on aerospace and other high-technology projects.

Jan joined BHO Legal at the beginning of 2019 on account of his background in the air and space law community, but BHO’s history with the technology stretches back much further. The firm was involved in the DroneRules.eu project funded by the EU Commission to provide information on drone-related laws and regulations across the EU, Norway and Switzerland. Insights from that history formed the baseline of Jan’s presentation that laid out the path of drone rules harmonization in Europe, detailed operational authorization, explained the new registration process and much more.

Jan joined BHO Legal at the beginning of 2019 on account of his background in the air and space law community, but BHO’s history with the technology stretches back much further. The firm was involved in the DroneRules.eu project funded by the EU Commission to provide information on drone-related laws and regulations across the EU, Norway and Switzerland. Insights from that history formed the baseline of Jan’s presentation that laid out the path of drone rules harmonization in Europe, detailed operational authorization, explained the new registration process and much more.

We connected with Jan to further explore many of the insights that he shared during his presentation but also detail how these new regulations will impact drone operators of all types in 2020. We asked him about whether or not it makes sense to make comparisons between these new regulations and Part 107, to explains the three categories of UAS operations in these new rules, what he’s looking forward to seeing come together with drone technology in Europe in 2020 and much more.

Jeremiah Karpowicz: How have you seen attitudes and approaches around drone technology evolve over the past few years?

Jan Helge Mey: What I see is that besides the aerospace companies and institutions that have taken an inherent interest in drones, we’re seeing more and more technology companies that make drones or drone-enabled data part of their value-creation chain. Drones are now considered to be a new means of “getting the job done” while also providing additional opportunities to expand a business.

On the other hand, the potential risk of unlawful drone use is becoming a major topic, particularly for operators of critical infrastructure operators but also “ordinary” companies. It’s gotten them to ask how they can protect themselves from drones.

Your presentation at INTERGEO 2019 was titled “The new EU drone rules – how to continue your business after 2020” and it showcased some key insights for the audience. At a high level, what did you want to convey to the audience about the path of drone rules harmonization in Europe?

Harmonization of drone rules has taken a giant leap in Europe, but – not surprisingly – there are still more steps to take, and I wanted to convey that concept to the audience. Additionally, the rule making competence of the European Aviation Safety Agency was expanded to cover practically all civil unmanned aircraft including those with an operating mass of less than 150 kg which were previously the domain of the Member States.

Europe is now in a position to build the framework on solid ground. It immediately started to do so by putting in place regulation on technical requirements, UAS operations, remote pilots and operators in the open and specific category. More detailed regulation will soon begin to pour in, especially with respect to operating under standard scenarios that will not require prior authorisation as well as regarding the certification of drones and unmanned traffic management.

Much of that is tied to the announcement by the EU Commission around new rules for drone implementation across the continent, and we wrote about how this development finally established common drone rules for all of Europe. Is it that simple though?

Yes and no.

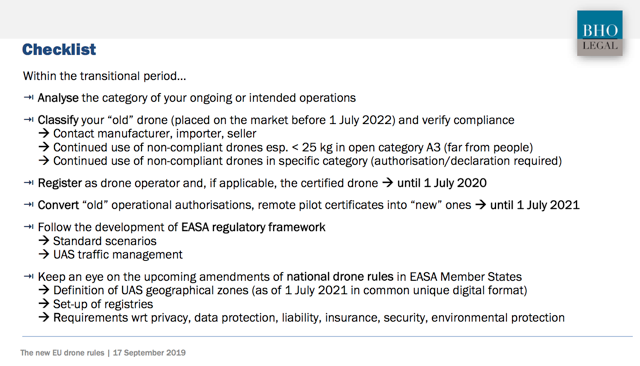

Yes, because the legislation put in place establishes common drone rules throughout Europe. The EU Commission Delegated Regulation 2019/945/EU and the Implementing Regulation 2019/947/EU on technical requirements and operations primarily in the open and the special category will become fully binding at the end of the transitional period in 2022. However, certain requirements such as registration as UAS operator will already be applicable as of 1 July 2020. The regulatory framework is being further implemented through guidance material and acceptable means of compliance issued by EASA as well as further amended e.g. with respect to standard scenarios, traffic management and certification.

No, because the Member States reserve the competency in various fields. Regulating drones with respect to security, environmental protection, data protection, liability and insurance remains largely their domain. It will be especially left to the Member States to define the specific UAS geographic zones and to set up airspace in which UTM, the so-called U-Space Services, will be offered.

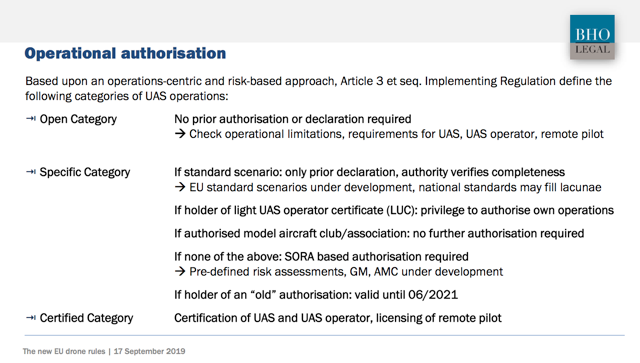

Can you briefly discuss the significance of the breakout of the three categories of UAS operations: open, specific and certified? Which categories should commercial operators be most concerned about and focused on?

The categories of UAS operations are an element of the operations-centric and risk-based approach adopted for the EU drone rules. Which category to focus on for commercial operations depends on the specific business case.

Operations in the open category have the advantage that they do not require prior authorisation. The downside is that they are restricted to drones in the UAV classes C0 to C4 limited to a max. MTOM of 25 kg. More importantly for a lot of use cases, only VLOS and EVLOS operations fall under the open category.

Wherever the confinements of the open category cannot accommodate the use case, one can get rid of these shackles by operating in the specific category. If the operations comply with a standard scenario, a mere declaration to the authority is sufficient. Otherwise, the operator needs to undertake a Specific Operations Risk Assessment based on JARUS SORA V2.0 and requires prior authorisation. The first two standards scenarios are expected to be adopted in February 2020, for VLOS in urban areas and BVLOS in rural areas.

Operations under the certified category will be necessary for high-risk scenarios that are comparable to manned aviation such as the transport of people and carriage of dangerous goods.

Some have compared this development to being like Part 107 was for drone operators in the United States. Do you think that’s an accurate comparison?

Operation of small UAS under Part 107 in the United States is similar to the operation in the open category in Europe. However, the comparison limps.

For example, the European drone regulatory framework covers all civil UAS, including model aircraft flown for hobby or recreational use as well as commercial aircraft because from a risk-based and operation-centric perspective the motivation for the operation does not really matter. The general operational limitations in the open category, such as keeping the drone in VLOS up to a max height of 120m and in a safe distance from people and no carriage of dangerous goods, are complemented for each of the three subcategories A1 to A3 and then tailored to five different UAS classes C0 to C5. Those are different levels of remote pilot competence and UAS operator responsibilities in order to achieve an overall acceptable level of safety.

The drone rules that were put in place in Europe also cover the category of specific operations. Their characteristics are that they go beyond the limitations of the open category, be it a MTOM greater than 25 kg or BVLOS operations. These require an individual or standard risk assessment.

For a long time, the fragmented regulatory environment in Europe was cited as the reason that many held off on commercial drone adoption. That is to say, legally operating a drone for commercial purposes was different in Germany than it was in France. How does this development change that perception and reality?

The harmonization of the legal framework will certainly facilitate the drone market and even transborder operations. The new drone rules provide e.g. that operators only have to register once in Europe and not in every Member State. Certificates and authorizations are – in principle – valid in every Member State.

Yet, peculiarities will remain and it will take a while until everything works smoothly. The next milestones that further enables commercial BVLOS operations and UTM services are awaited eagerly.

What do you feel are the most noteworthy items for commercial operators from the new registration requirements that will be applicable as of 1 July 2020?

Operators need to register themselves and not necessarily their drones until 1 July 2020 – provided that Member States manage to set up the registries in time. The operators must display the registration on their entire drone fleet and will mostly have to enable remote identification. Only drones that require certification need to be registered as such.

Operators and remote pilots should also convert any “old” authorisations and certificates in time while keeping an eye on the future development of both the EASA regulatory framework and the national drone rules. An interesting option for commercial operators will be to obtain a light UAS operator certificate (LUC). The LUC comes with privileges to authorize one’s own operations.

Do you believe that the forthcoming EASA Opinion on U-space should have a major impact on how enterprise organizations in the present move forward with the adoption of drone technology?

We have participated in the consultation process and provided input to EASA based on its draft opinion for the high-level regulatory framework for the U-Space. The importance of laying the groundwork for UTM services cannot be underestimated as an enabler. This could be heard in unison at the recently completed Amsterdam Drone Week. In light of the ongoing discussions about a complex system, the EASA opinion is now supposed to be published in March 2020.

What is the significance of EASA’s publication of the Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) and Guidance materials (GM) for the Regulation on UAS operations in the open and specific category? What kind of an impact will this make in the short and long term?

AMC and GM are ordinary tools that EASA has at its disposal. They play an important role in facilitating the regulatory processes. If you follow an Acceptable Means of Compliance you are presumed to be in compliance with the requirement. You may choose a different means, but then the burden of proof is entirely on you. Guidance Material helps to understand the rules and requirements, but is also not binding.

If an enterprise organization has held off on the adoption of drone technology on account of regulatory uncertainty, do you believe the developments we’ve been talking about should compel them to consider adoption in 2020?

The lawyer speaking, enterprises should always make a legal risk assessment prior to making significant investments. The results could also inform the design of the use and business case and the project planning. The legal framework is still evolving but the fog is clearing. If an enterprise has held off although it clearly sees a potential derived from drone technology, 2020 is certainly a good time to start.

What’s one new development or change you’re looking forward to seeing take shape for or with drone technology in Europe in 2020?

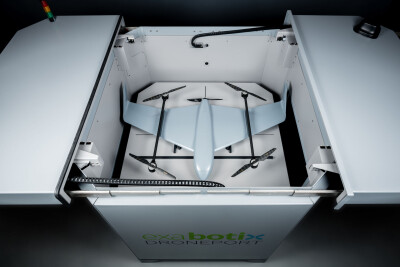

I think it would be great if drones become a normal part of our lives, our policy and business decisions. I would like to see that life- and planet-saving operations are heavily rolled out in 2020 using automated or even partly autonomous vehicles, be it transport of critical goods, enablers for smarter agriculture or safer inspections of infrastructure.

And, yes, I would like to have an air taxi flat rate.

Comments